There are many file types in Linux, and we’ll learn to find the file type in the Linux terminal in this article. It’s not terribly difficult and is a good basic article, with a command not that widely discussed. It’s a good time to learn.

Let’s start at the beginning… As many of my readers are new, there’s some stuff you ought to know.

First things first, everything in Linux is a file. I realize that that may confuse some folks new to Unix/Linux, but it’s true. If you don’t know how this works, click this link. That should explain it well enough.

Linux also uses the whole Magic Bytes thing. You can click here and learn about Magic Bytes. To explain it a bit differently than Wikipedia – it’s why you can make a text file without an extension and still have it open with a text editor when you click on it. The system sets Magic Bytes that mark the file as being of a certain type.

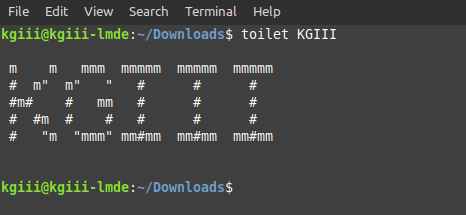

Well, there’s a tool that you can use in the terminal to find a file type. Amazingly enough, that tool is called ‘file’. The man page for which is clear:

file — determine file type

Yup, that’s the tool and that’s what it does. It’s pretty accurate and works with a number of file types. It checks things like whether the file is an empty file, what response it sends when queried, if it has Magic Bytes, and the language used in the file. It’s pretty comprehensive.

Find The File Type:

Obviously, this requires an open terminal. After all, we’re finding the file type in the terminal. That kinda needs an open terminal! Just press

Now, with your terminal open, and enter the following command. I’m pretty sure this will work on any desktop Linux!

1 | file ./.Xauthority |

It’ll happily spit out that you have a data file on your hands.

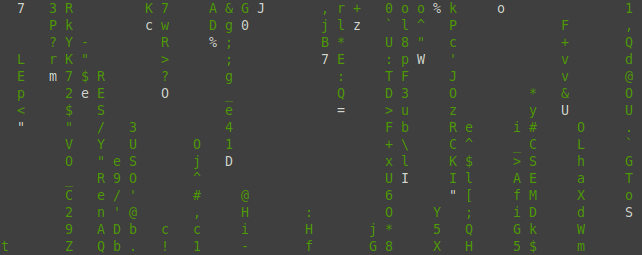

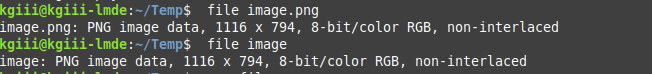

But, here, let’s see if we can fool it. Grab an image and call it image.png (or whatever extension) and run file <filename.extension> to see the output. Now, rename the file to just plain ‘image’ and run the command again (sans extension). What does it tell you? It should look something like this:

Go ahead and try to fool it. Rename it image.txt and try it again. Pretty neat, huh?

I don’t need to patronize, by now you get the idea. You see what it can do. Well, there’s a bit more. You can create a text file with a list of files in it (with their path if in different directory) and the run file on that file you created – just make sure it’s a plain text file that you created. It’ll happily output the types of all the files listed inside.

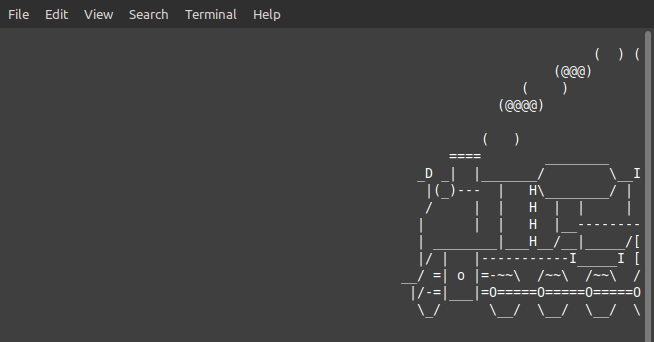

You can also use the whole wildcard thing. You can get all the file types in a directory with this command:

1 | file * |

If you want all the files starting with the letter I, you’d do this:

1 | file i* |

If you want, you can even use it on compressed files. For that, there’s the -z flag. It looks something like this:

1 | file -z <filename.tar.gz> |

It’ll spit out some information, perhaps letting you know the minimum version of your archive manager needed to open it. It doesn’t give you information about the compressed files, however. To do that, you’d have to extract the files first.

Closure:

And there you have it. You have yet another article! This one shows you how to find the file type in the terminal, and is a handy tool indeed. I normally take the entirety of January off, but I can’t do that this year. This year, I must ensure there are articles. Maybe next year! The good news is I can author these things with a wee bit o’ the wine in me. So, there’s that!

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.