This article won’t need to be all that long but it might be complicated as we discuss how to avoid storing commonly used commands in your Bash history. Yes, it’s a long title.

This is also a bit contrary. It is one of those things that is easier done than said. It’s a very wordy thing, after all. I’ll do my best to describe what’s going on and why you might want to do this.

In this case, Bash stands for Bourne Again Shell. This article only applies to those who are using Bash. Bash is not the only shell available and people may opt to use other shells. If you’re one of those people, I don’t think this is going to work for you.

When you’re using the terminal, you’re using Bash. The commands you enter into the terminal are stored in ~/.bash_history, a hidden file in your home directory. We’ve discussed some of this before.

How To: Have Infinite Bash History

Playing With Your Bash History

How To: Not Save A Command To Bash History

How To: Reload Your .bash_profile

Well, you may type common commands, such as uptime. You may not want to store that command in your Bash history. Do you want to store every time you’ve typed the ls command?

You don’t have to. You have options!

What can you do? Well, you can tell Bash not to store certain commands in the ~/.bash_history file. This is actually a simple operation. To avoid storing commonly used commands in your Bash history, you need only to edit your ~/.bashrc file. I’ll show you how!

Man, this is going to impact the layout…

How To Avoid Storing Commonly Used Commands In Your Bash History:

Yeah, no amount of formatting is going to make that look good.

Anyhow, if this isn’t obvious, you’re going to learn how to do this in the terminal. You could edit your ~/.bashrc file with your favorite GUI editor but we’ll be doing this entire thing in the terminal.

As such, you should have an open terminal. More often than not, you can open your terminal by pressing

So, first, we need to use Nano to edit the ~/.bashrc file. That’s an easy command:

1 | nano ~/.bashrc |

Use your arrow button to navigate to the bottom of that file. Go to the absolute bottom and press enter to start a new line. You can press that button twice to provide some separation and to make it easier to read.

Now, let’s say we don’t want to store the ls, uptime, or touch commands in your Bash history file. We’ll use those as our examples. You should also probably leave a comment in your ~/.bashrc file so that you can easily identify what the code does and remember why you added it. That’s also useful if there are other users.

So, add the following lines:

1 2 | # ignore commonly used terminal commands export HISTIGNORE=":ls:uptime:touch:" |

Next, save that file. As we’re using Nano, you save the file by pressing

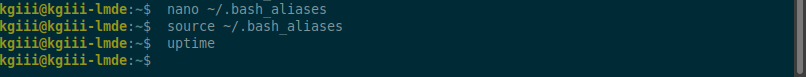

Next, you reload your ~/.bashrc file much like you reloaded your Bash profile (which was a link in the intro, should you wish to read it). You reload the ~/.bashrc file with this command:

1 | source ~/.bashrc |

That should reload the file. If it doesn’t, you can close all your terminal instances and open a new one. If that doesn’t work, you can log out and log back in again.

Anyhow…

Commands starting with :<command>: entries you used will not be stored in the ~/.bash_history file. If you type a command starting with those entries, it will be ignored, meaning they won’t clutter up your ~/.bash_history file with commands you’re already familiar with or commands that don’t need to be stored for things like auditing or security reasons.

It’s pretty simple to do, though it’s a bit of a pain in the butt to explain. This is how you avoid storing commonly used commands in your Bash history – something nobody is going to search for. (If you did find your way here via a search engine, be sure to leave a comment. I want to know who you are!)

Closure:

I realize that this is an awkward article and I’m okay with that. This isn’t something everyone is going to bother with, especially those people who don’t do much in the terminal. Still, it’s possible to avoid storing commonly used commands in your Bash history and now you know how.

Then, someday, someone’s going to search for this exact string of characters and, hopefully, they’ll find this article. I hope this satisfies their curiosity and helps them reach their Linux goals! If you did read this and find it valuable, you can always leave a comment.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.