Today’s article is going to teach you how to check your hard drive temperature (in Linux, of course). There are a number of ways to do this, so we’ll just cover one way in this article. It may seem complicated, but it’s not. This should be a pretty short article.

You should have a general idea of the temperature of components within your computer. The components have various operating temperatures and keeping them within spec means they’ll last longer and give you better performance.

Hard drives generally have temperature sensors and we’ll be using ‘hddtemp’ in the terminal to check your hard drive temperature. It won’t work with every hard drive, but it may work with yours. It’s a pretty easy application to install and use, so we’ll go over it as though you’re using Debian/Ubuntu/Mint or something that uses apt. A quick check says you have this available for other distros.

By the way, ‘hddtemp’ defines itself accurately enough, like so:

hddtemp – Utility to monitor hard drive temperature

Which is, as the article intends, exactly what we’re going to do…

Check Your Hard Drive Temperature:

This article requires an open terminal, like many other articles on this site. If you don’t know how to open the terminal, you can do so with your keyboard – just press

With your terminal now open, let’s install ‘hddtemp’:

1 | sudo apt install hddtemp |

Next, we want to start it as a service:

1 | sudo systemctl start hddtemp |

And we’ll want to have ‘hddtemp’ start with the boot process:

1 | sudo systemctl enable hddtemp |

That’s about it for the installation. Now all you need to do is know which hard drive you want to check. You can get a list of hard drives by running:

1 | lsblk |

Next, you’ll run ‘hddtemp’ as a privileged user and use the path to the drive you want to check. So, it’d look a lot like this:

1 | sudo hddtemp /dev/sda |

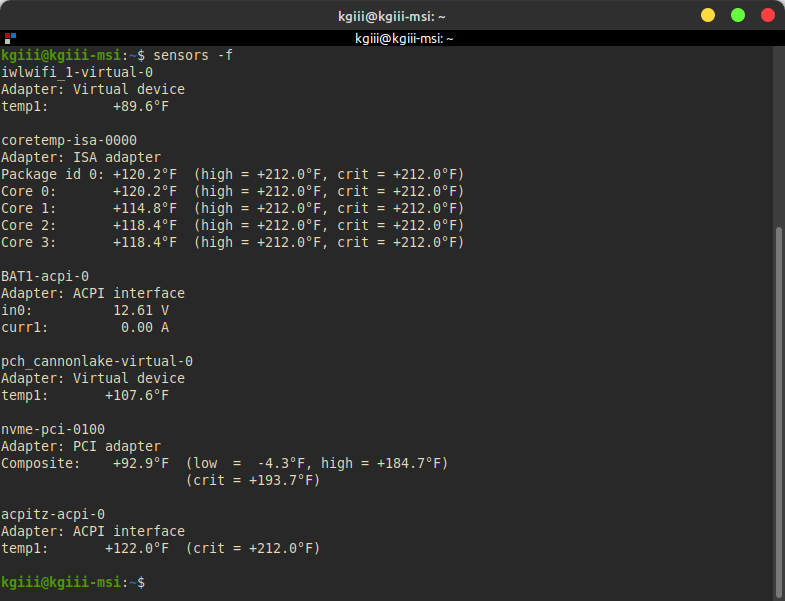

If you’re in luck, it’ll spit out the drive temperature. If you prefer Fahrenheit, the command should look similar to this:

1 | sudo hddtemp --unit=F /dev/sda |

That’s really all there is to it. You can check the man page for other options, but this is how most folks are going to use ‘hddtemp’ on their own local computers.

Closure:

Well, this was a short article. I have a bit of a stomach ache, so picked one that’d be shorter than most. Ah well… At least now you know at least one way to check your hard drive temperature. That’s always a good thing.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.