Today, we’re going to examine one way to check for bad sectors on your disks. Once again, it won’t be a particularly taxing article, but it’s something everyone should know how to do. This being Linux, I’m sure there are alternative tools.

Hard drives, from spinning platter to solid-state, are divided into sectors. Sometimes, these sectors go bad. The disk’s software manages this to some extent, and actually has more space available than listed so that it can make up for bad sectors as time passes.

But, you still get bad sectors. It’s just the nature of the game, and no disk drive is immune to this. All you can do is accept them and, in some cases, repair them.

See, there are two types of bad sectors. The first is a hard bad sector, which is hardware related and can’t be fixed. The second is a soft bad sector, which is a software issue and it can be fixed. I’ll someday write an article about how to fix soft bad sectors, but I won’t bother getting into that today.

With all that in mind, the tool we’ll be using is appropriately named ‘badblocks’, which describes itself thus:

badblocks – search a device for bad blocks

Badblocks has a variety of uses, so you can always get a head start on this article by reading the man page.

1 | man badblocks |

So, with that already covered, let’s just jump into the article.

Check For Bad Sectors:

This article requires an open terminal, like many other articles on this site. If you don’t know how to open the terminal, you can do so with your keyboard – just press

With your terminal now open, you should probably identify your drives with the following command:

1 | sudo fdisk -l |

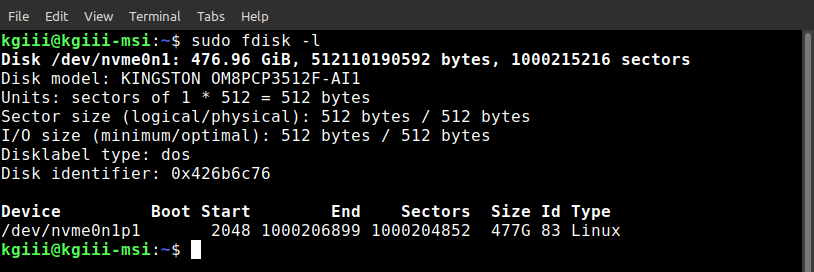

The output of this may look a bit like this:

As you can see, it’s listed as /dev/<device_ID> and that’s the information you want to hold onto.

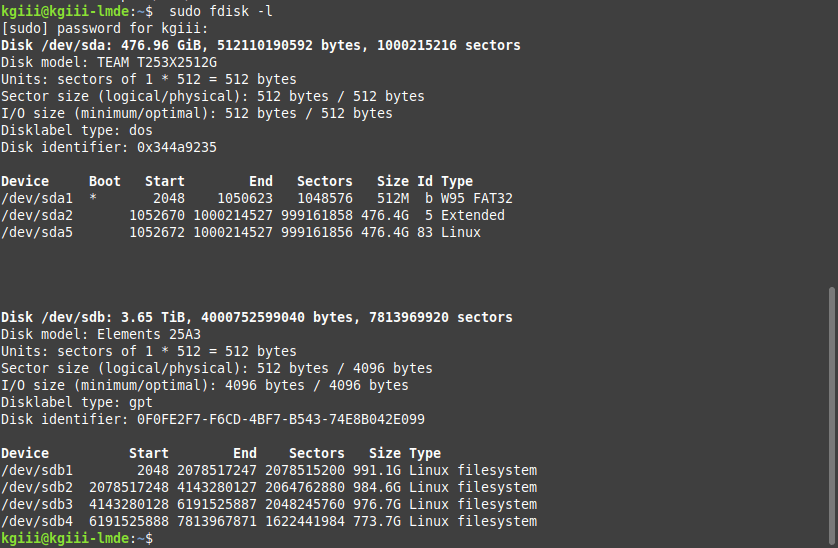

Sometimes, it’s a lot more complicated, and will look something like this:

As you can see, they’re all start with ‘dev/sd*‘ and end up as /dev/<device_ID>. The system I ran badblocks on is quite a bit more complicated than the output from the laptop I used in the first instance.

Now, you want to scan your individual device to check the for bad sectors. That’s actually just a simple command. You can use:

1 | sudo badblocks -v /dev/<device_ID> |

The -v ensures the output is verbose and sent to the screen. You can also write that data to a text file for reference. To do that, you just use a command similar to this:

1 | sudo badblocks -v /dev/<device_ID> > badblocks.txt |

Then, you’ll have a badblock.txt file you can refer to, showing you information about any bad blocks. I wanted to show you the output from a disk with bad blocks, but I don’t appear to have any to show you. I tried quite a few, but it was a no-go. Ah well… You’ll figure it out easily enough. It’s not even a little hard to check for bad sectors!

Closure:

Yup… You have another article. This time you learned how to check for bad sectors, a pretty handy tool – especially if you’re finding corrupt files on your disks. If you are facing corrupt files, this would be the first step I’d suggest taking.

Anyhow, the show does go on and you got a new article. I am more or less feeling just fine now, just some lethargy and not a whole lot of energy. Sweet!

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.