Today’s article shouldn’t be all that difficult for even our newest users but is limited to those who want to change DNS servers to something other than the default. This is easy enough to do, but obscure enough to warrant an article of its own.

First, let’s have some fun. I’m going to ask ChatGPT to tell you about DNS in just two paragraphs. So, let’s see what the AI has to say:

First, what is DNS?

DNS, or the Domain Name System, is a fundamental protocol used in computer networks to translate human-readable domain names into machine-readable IP addresses. It serves as a decentralized directory system that enables users to access websites, send emails, and perform various network activities using familiar domain names instead of numerical IP addresses. When a user enters a domain name in their web browser, the DNS resolver (typically provided by the Internet Service Provider or ISP) initiates a series of queries to locate the corresponding IP address. The resolver communicates with DNS servers, starting from the root servers, then the top-level domain servers, and finally the authoritative name servers associated with the requested domain. Through this hierarchical process, DNS ensures efficient and accurate resolution of domain names, facilitating seamless internet connectivity.

DNS operates through a distributed database system known as the DNS namespace. This namespace is organized hierarchically, with the root domain at the top, followed by top-level domains (TLDs) like .com, .org, or country-specific domains such as .us or .uk. Beneath the TLDs, there are second-level domains, and further subdivisions like subdomains. Each domain has authoritative name servers that store the IP addresses associated with the domain names they manage. DNS resolution occurs through recursive queries, where the resolver traverses the DNS hierarchy to find the authoritative name servers responsible for the domain. Once the IP address is obtained, the resolver caches it for future use, reducing the need for repetitive queries. DNS plays a crucial role in the functioning of the internet by providing a scalable and efficient method for translating domain names to IP addresses, enabling seamless communication and accessibility across the network.

Wow! That’s pretty accurate. I’d have just resorted to describing DNS as the telephone book of the internet. You look up the name you want to reach and DNS tells you the number. In this case, the number is the IP address.

All in all, I’d say ChatGPT did a pretty fine job.

Change DNS Servers:

There are a variety of reasons why someone would want to change DNS servers to something else. They may get updated more quickly, weed out junk domains, or even remove ads and things like that. Maybe you want to weed out inappropriate material because you have children. Perhaps you have some custom configurations needed to traverse your complex local network. There are all sorts of reasons why you might want to change DNS servers.

See, as alluded to above, it’s perfectly possible to run your own DNS server (see Pi-hole for one such example). You can also use DNS servers provided by various third parties. For example, CloudFlare and Google offer their own DNS servers that are free for you to use. There are other choices, but this isn’t an encyclopedia writ large, so I’m going to just include those two. You can use your favorite search engine to find more.

So, let’s say you don’t like using a DNS server provided by your ISP. Perhaps you do this because of privacy issues, though you can look into DNS over HTTPS if you’d like. Perhaps you just don’t find them updated quickly enough or you’ve found they contain errors. (They do sometimes have issues and have even been known to be exploited in the past.)

NOTE: We’ll be using ‘nano‘ for this exercise. We’ll also default to Google’s public DNS servers, but you can substitute with whatever you find available.

Well, the first step you’re going to take is opening your terminal. You can do that by just pressing

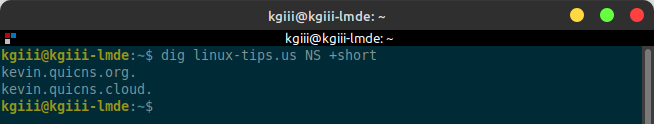

The file we’ll be editing doesn’t actually exist on most distros. That’s not a problem, because we’ll be making that file with nano. With your terminal open, enter the following command:

1 | sudo nano /etc/resolv.conf |

That should be a perfectly blank file and you’ll want to enter the following (again, using Google’s public DNS servers) to change DNS servers:

1 2 | nameserver 8.8.8.8 nameserver 8.8.4.4 |

Then, you’ll save the file with Nano. That’s pretty easy. To save this new resolv.conf file with nano, you just press

Next, you’ll need to reboot. I know this will pain some of you, but I’ve yet to have a sure way to effect these changes other than rebooting. So, you’ve gotta do that. Try this command:

1 | sudo reboot |

Now that you’ve managed to change DNS servers, you should be able to browse around much as you normally would. Remember, the people in charge of the DNS servers are the ones that decide where you go when you enter an address into the address bar and smash that enter button.

Be sure to use a company you trust to provide those services and be sure to verify your internet is still working properly. If it’s not working, you can remove the file and reboot or you can edit it again and try rebooting again. It shouldn’t be a problem in reality, this isn’t anything all that complicated.

Closure:

So, there you have it. It’s yet another article. This time around we discussed how to change DNS servers – along with some reasons as to why you might want to. If you have a spare bit of hardware kicking about, you can make your own DNS server and point to that with the internal addresses you’d be using. It’s nothing too painful and I think even beginning Linux users can follow along easily enough.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.