In today’s article, we’re going to learn how to adjust swappiness. It’s something you might want to do, as many don’t like the initial value set by the developers. It’s relatively easy.

I’ve written about swap before. I think you’ll find the best information in my recent article telling you how to remove a swap file. In that article, I tell you why I still use a swap file – even when I have lots of RAM available.

The reason for that boils down to how a swap file isn’t just some place that the kernel sticks things when you’re out of RAM. It has other uses as well. I figure I’m not smarter than the kernel and evidence tells me that the kernel uses swap even when there’s all sorts of RAM available. So, I use a swap file (not a swap partition these days). You might also want one if you plan on using advanced power management features like hibernation or sleep.

Anyhow, one of the only settings you can change regarding swap is the ‘swappiness’ value. That setting is basically how aggressively the kernel will use swap. The higher the number, the more the kernel will use swap. The lower the number, the less the kernel will use swap. It’s pretty basic in theory.

I don’t actually normally adjust the swappiness value. It works just fine at the default setting, so it doesn’t seem to me like I need to adjust it. Other people adjust it, and that’s fine. Either way, I’m going to tell you how to adjust the swappiness value. You do what you gotta do.

Adjust Swappiness:

This article requires an open terminal, like many other articles on this site. If you don’t know how to open the terminal, you can do so with your keyboard – just press

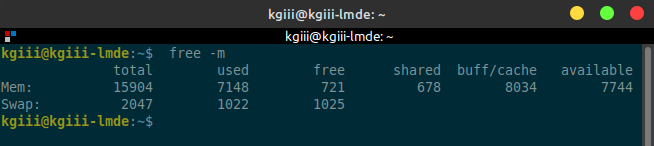

With your terminal open, let’s see what value swappiness is set at before we decide to adjust swappiness. Enter the following command:

1 | cat /proc/sys/vm/swappiness |

The default is usually 60, at least in the Ubuntu world, and some folks think that’s too aggressive. That value is easy enough to change. But, what I’d suggest doing is adjusting the value temporarily so that you can see what happens when you adjust swappiness. To set the value temporarily, you can just use this command:

1 | sudo sysctl vm.swappiness=30 |

Adjust the ’30’ to any number you want between 0 and 100. Both extremes are likely bad, but I’ve used values as low as 10. You could even set it to 0, which should stop the kernel from swapping anything.

Once you find a swappiness value you like, you can make it a permanent change to your system. That’s pretty easy. You just:

1 | sudo nano /etc/sysctl.conf |

Add the following lines of text:

1 2 | #set swappiness vm.swappiness=30 |

Use your own value if it’s not 30 and save the file. To save a file in nano, press

You can then reboot, or just wait until your next reboot, and the new swappiness value will be used. If you don’t feel like rebooting immediately, just adjust it temporarily and reboot when it’s convenient for you.

Closure:

There you have it, another article! This one has you learning how to adjust swappiness to a value that you can work with. I’d encourage folks to read the linked swap file article to see why I use a swap file even when I have gobs of RAM. If nothing else, using one won’t break anything.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.