This article will show you how to get better network diagnostics with MTR, a tool called “My Traceroute” that combines both traceroute and ping into a single tool. MTR is a pretty handy tool that’s likely installed by default and a tool that even regular users should have in their toolbox.

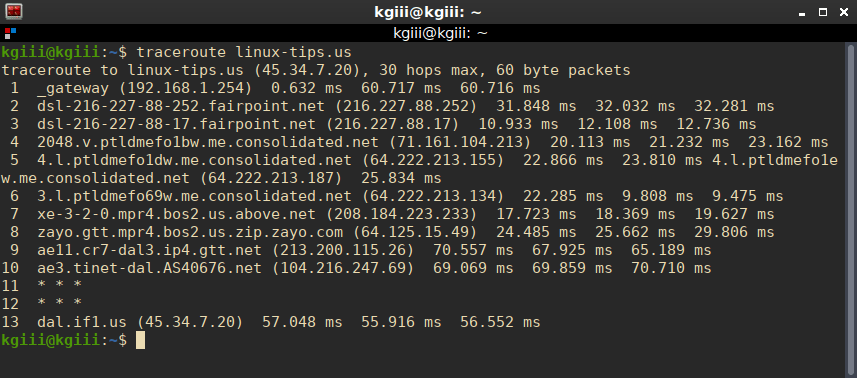

You may remember that I wrote an article about traceroute. If you don’t know what traceroute is, it’d be in your best interest to go read that article, as I will not really be duplicating the work that went into writing that article.

As of yet, I have not yet written an article about ping. Ping is a terminal-based tool, used to time how long it takes for your device to send and receive packets to and from another device. It’ll also tell you if there are packets being dropped along the way. You can use it pretty easily. Here’s a very basic ping command:

1 | ping linux-tips.us |

(You can use

The output from that command is pretty self-explanatory. The numbers you’re probably most interested in are all the way on the right, and denote how long it took for a round-trip message to complete in milliseconds. Online gamers are often interested in their ping times. This is because a higher ping may mean they may lag behind their competitors. In this case, lower is better.

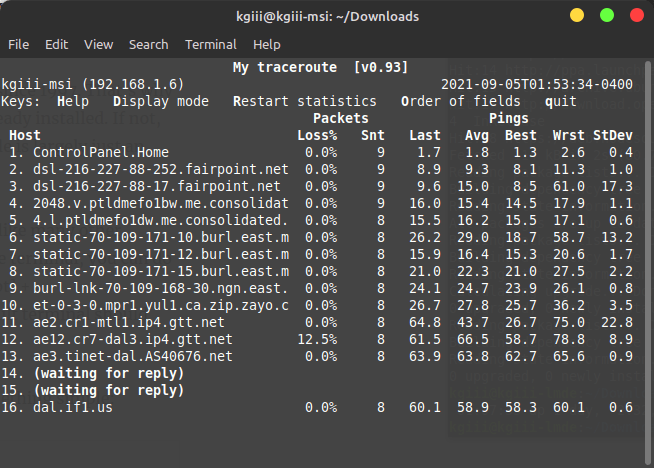

Well, MTR combines the two, traceroute and ping. It’s pretty awesome. You’ll see!

Network Diagnostics With MTR:

So long as you understand both ping and traceroute, there’s not much more this article can teach you. MTR is pretty basic in its output, easily understood by all but the novice users. Anyone with any networking history will immediately grasp the importance of MTR.

MTR isn’t a new tool, having been around since 1997. I won’t be covering how to install it. MTR’s likely already installed. If not, it’ll be easy enough to install it. If anything, this article is largely just an excuse to make people aware of it.

This article requires an open terminal. If you don’t know how to open the terminal, you can do so with your keyboard – just press

Now, with your terminal open, try:

1 | mtr linux-tips.us |

It should look something like this:

There’s some options while it is running. The H, D, R, O, and Q keys all have functions, listed right there after “Keys:”! There are a few options when starting MTR, a whole lot of options. You can find those options by running man mrt. I’ll cover a couple of interesting options here.

If you want to limit the number of pings, you use the -c flag and then add the number. In the example below, I have chosen 5.

1 | mtr -c 5 linux-tips.us |

You can also just show IP addresses, not resolving the hostname. Like so:

1 | mtr -n linux-tips.us |

If you want to show both IP addresses and resolved hostnames, the flag is -b.

1 | mtr -b linux-tips.us |

There’s more that you can do with it, but mostly you can use it to find where along the line the traffic stops. If it’s on your end, you get to do something about it. Otherwise, I suppose you’re at the whim of the MITM. So, give the man pages a look and let me know in a comment if you already use this tool and how you use it.

Closure:

And there’s another article. Woohoo! It’s not just another article, but it’s an article about doing network diagnostics with MTR. It’s not as hard as one might think to come up with ideas for articles. Sometimes, I just use a tool and then realize it may make for a good article. That’s what happened in this case.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.