You might not know it, but you actually have a calendar in the terminal. It’s surprisingly handy. Though, to be clear, I pretty much only use it when I’m already in the terminal – such as when I’ve used SSH to connect to a remote server.

So, it’s useful (to me) while I’m already in the terminal. The rest of the time, I’m in a GUI desktop environment and there’s a calendar to be had just by mousing over the time. There’s also Thunderbird’s calendar and I use that a great deal. It cal command is of limited value, which is just fine.

The tool we’ll be using is called ‘cal‘. The cal command is in wide use today and has been with us for, at the time of this writing, more than fifty years. It’s a pretty straightforward command and its longevity speaks towards its usefulness for a subset of Unix/Linux users. It describes itself like:

cal, ncal — displays a calendar and the date of Easter

And it does (sorta) tell you when Easter is – for both western churches and the Orthodox churches. See? It’s already doing what it says on the tin! It only gets better from here!

We won’t really be covering ncal, which is useful if you’re trying to find things like the number for the day of the year. While that might be useful to some, it’s not useful to most and those folks can easily read the man page to learn more about it.

Anyhow, on to the article about the calendar in the terminal!

Calendar In The Terminal:

As you can see, this has to do with the calendar in the terminal, so you’re going to need an open terminal. If you want, you can just press

With your terminal now open, you can start with the absolute basic command, which will show you a calendar with today’s date highlighted. It’s really easy, it’s just:

1 | cal |

If you want to show the last month, this month, and next month, you can do that too. The command to do that is:

1 | cal -3 |

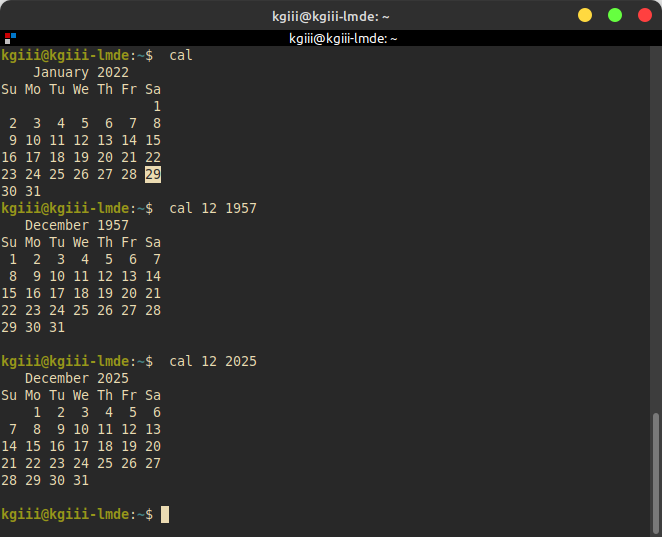

If you want to see a month from time past, or in the future, you can do that. The format for that is <mm> <yyyy> and it’s useful for both months past and months future. It looks something like this:

1 | cal 12 3030 |

The previous commands (sans cal -3) will give an output similar to this:

But wait! There’s more! You can show the entire year in the calendar by just using the -y flag. It looks like this:

1 | cal -y |

That command can be modified. To show a different year, it’d look a little something like:

1 | cal -y 2028 |

By default, the calendar in your terminal uses the Gregorian calendar. If you want the calendar in your terminal to use the Julian format then you just use the -J flag.

On top of that, it really will tell you when it’s time to celebrate (assuming you do) Easter. For some reason, I can’t get ‘cal’ to show Easter – but you can still make it work. To show it in Gregorian (western churches) format, it’s just ncal -o or for Julian dates you’ll just use ncal -j.

Closure:

See? I told you that you had a calendar in the terminal! It’s not entirely useless and can be useful when you’re full-screening your SSH sessions, or something of that nature. If you regularly work in the terminal, this is a handy tool to add to your toolbox. Most of the time, you’ll probably only need three letters to have a useful calendar appear in your terminal.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.