You may not think so, but everyone can meaningfully help their favorite distro. Someone has to beta-test Linux, and most everyone can do so. Here’s one way that you can help.

You don’t have to be a programmer, being able to code isn’t mandatory. It’s not even a requirement that you have spare hardware to test with. Going gung-ho and testing daily isn’t even a requirement. You just need to have some time that you’re willing to give back to the projects that have given you so much.

I don’t tend to do half-measures, so I’ve thrown myself into the task. The amount of learning I’ve done since starting is probably the most I’ve done since I was just a Linux beginner. If you like learning, then your ability to help knows no bounds.

Why I Beta-test Linux:

About a year ago, I learned why Ubuntu stopped offering 32 bit versions. It wasn’t because 32 bit was old, nor was it because the devs hate 32 bit systems. The reason they stopped supporting 32 bit systems was because there were too few people willing to test on 32 bit systems.

Now, I don’t actually use any 32 bit hardware. In fact, I haven’t used 32 bit hardware since pretty much the first day 64 bit hardware hit the market. I had empathy for those who had to move to a shrinking pool of distro choices. I also realized that it could happen again, for other hardware or software.

That’s when I realized that I could do my part. It is when I decided that I’d look into the process. After some investigation, I made it known publicly that I’d be testing. By making the claim that I’d do so, it forced my hand into actually following through. The claim was made to them as much for their sake as it was for mine.

I’ve done it ever since. It takes maybe an hour per day to do it, and to do it well. I test on at least two different pieces of hardware, file my reports, and go on about my day. Sometimes I get more involved and test other things, but my usual activities are just testing the daily build.

How I Beta-test Linux:

This will, of course, be different for you – unless you want to beta test Lubuntu. In which case, this is pretty much how you’d do it. Though your method may still be different. My testing is “just” the live instances of Lubuntu.

The live testing is actually the longer of the two types of tests. If you’re doing the installation tests, you basically just install and make sure it reboots, perhaps ensuring internet connectivity works out of the box. If nothing breaks, you’re done.

Every day, at about 13:30 my time, I start refreshing the testing tracker URL. (That link is time sensitive. It won’t be the same for the next cycle. It’s largely for illustration anyhow.) What I’m looking for is the date to change on the download. When that changes, I know there’s a new daily build for me to test.

You don’t actually have to do this every day. You can do it when you have time, or closer to the end of the release cycle. You set the time and schedule.

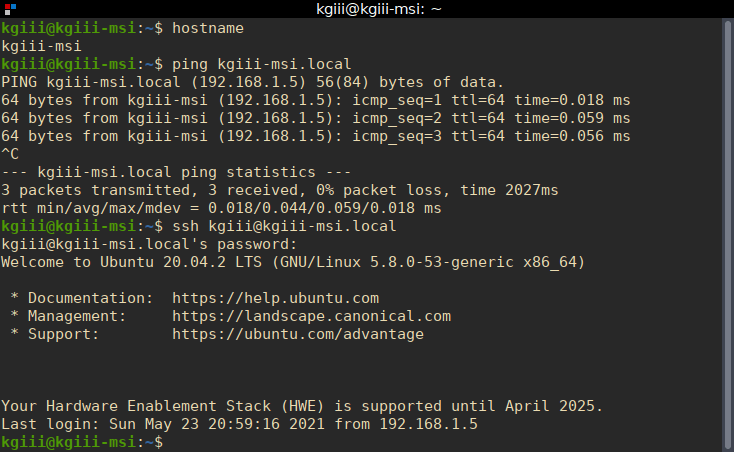

When the date changes and there’s a new daily build, I use the zsync option to save bandwidth. Using zsync means I’m only downloading the parts of the image that have changed. I not only do this on one computer, I do it on another computer. As mentioned above, I test twice.

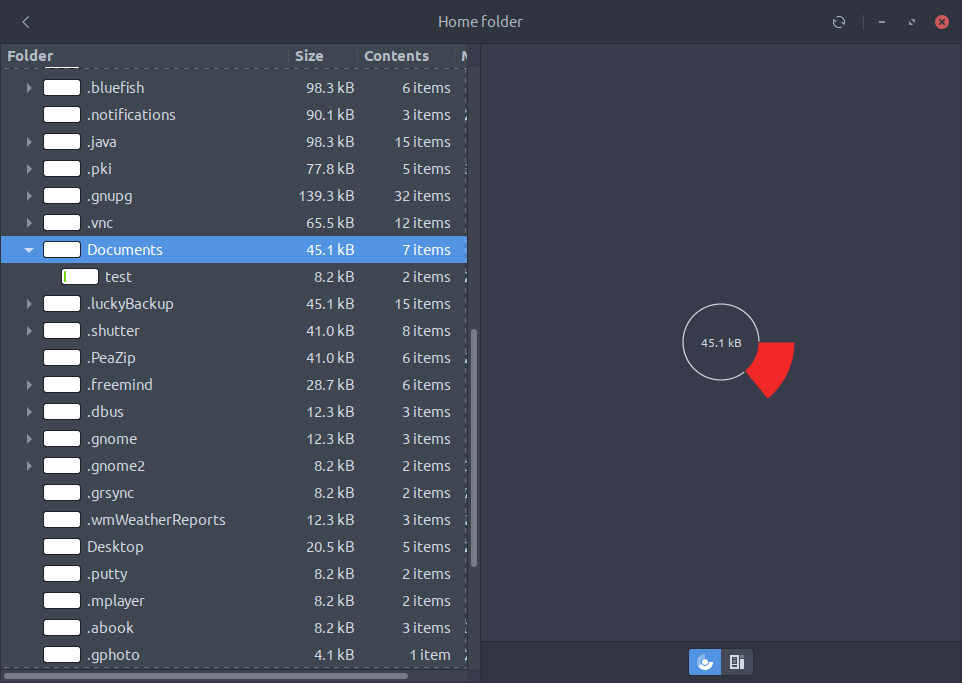

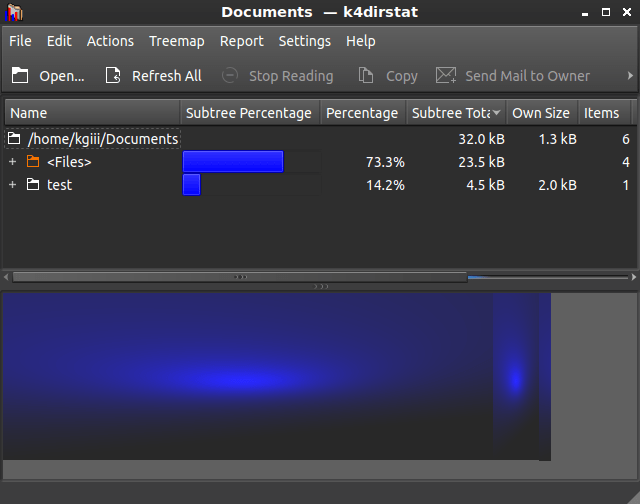

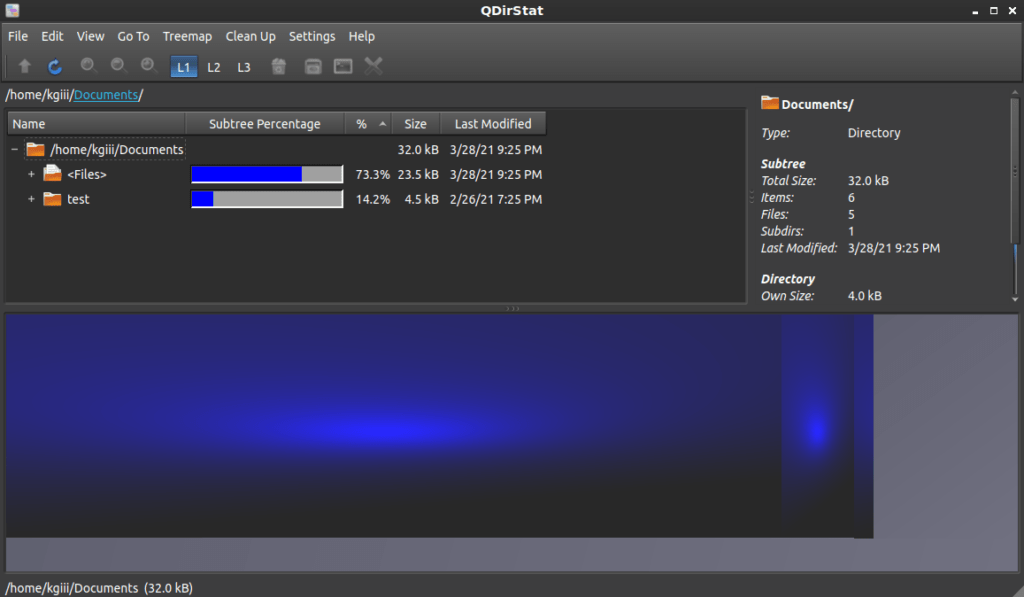

While I’m there, I also download the new manifest. The manifest is a list of all the files that are in the image (.iso, of course) and I use it to ‘diff‘ against the previous manifest. This tells me what has changed and what needs more attention and testing.

It’s at this time that I start filing my reports. Those will vary and depend on what your distro of choice is using. Mine are generally pretty basic and short, unless I find something amiss. If there’s something amiss, then that requires proper testing and bug reporting. That happens with less frequency than you might imagine, but it’s essential that you follow conventions and properly report bugs in a manner that the developers can use.

Later, those reports get closed, using a process where I mark the test as ‘in progress’ while testing and then close them as passed or failed when I’m done. Each report contains a list of existing bugs and any newly found bugs.

The Actual Beta-testing Linux:

When the two files are downloaded and reports opened as in progress, I’m ready to actually begin. On one machine, I’ll start writing the daily .iso to a USB drive and on the other I’ll use it to start a fully prepared virtual machine.

The testing done on both is remarkably similar. I also undertake the live testing and, as I said near the top, that one takes the most time. You’ll see why…

As I’m testing the live instance, the first two things I check and change are the screen resolution and the keyboard layout. Those will be the first two changes people are likely to make in a live environment, and so they’re the first two things I change and check.

The next task is checking the existing bugs. For example, there’s a bug in the terminal where it won’t actually open with the presets (two horizontal or vertical terminals). Another is a wonderfully odd LibreOffice bug that appears to have existed for quite a while before I noticed it. I’ll explain the LibreOffice bug and show it to you.

To trigger the bug, open every LibreOffice application up in order. If they stop appearing in the task bar after you’ve opened Impress, then you’re likely going to be able to trigger the bug. After they’re all opened, select the “Vivid” template in Impress – and watch all of the LibreOffice applications crash one after the other.

Watch, full screen should work if needed:

This particular bug was discovered because of how I do the testing. Nobody seems to know what the cause is and it doesn’t appear in every distro – but it appears, or manifests itself in some way, in a variety of distros. (I’ve tested, of course!)

So, once I’m sure that the existing bugs are still there, I do the rest of my testing. This means I open the menu, start at the top, and open everything. I don’t open them all at once, I open them by segments. First, I open all the Accessories, then Internet, then Graphics and Video, etc. applications at once. I make sure they all open and that they all close.

When there is a change noted by the diff I mentioned earlier, I make sure to check that application even more. I also pick a half-dozen, maybe a dozen, other applications to test more thoroughly. For those, it isn’t just checking to see that they open and close, I check that they do things like open the appropriate files, their preferences work, and that the application does the job it was meant to do.

Most of the time, there’s nothing doing. It’s exactly the same as it was the day before. Those days are the easiest. You just file the reports and you’re done for the day. If there are new bugs, you have a bunch more work to do.

In the case of a new bug, you need to file a proper bug report. More importantly, you need to make sure it’s a bug. To do this, you’ll test against everything you can think of. You’ll even test against other distros to see if the bug also exists in those distros. It is also worth installing the beta (preferably in a VM) to test to see if the bug is in both the installed and in the live instance. You want to narrow it down as much as you can, making it easier for the devs to fix.

The forms and paperwork you’ll be doing will vary. They won’t be just like the Lubuntu system, which is based on the Ubuntu system. You’ll need to connect with someone on the team, someone familiar with the process, to make sure you’re doing it right.

In my case, I call my connection my ‘mentor’, though that can sometimes be a formal term. They’ll need to be someone you get along with, because you’re going to interact with them fairly often as you learn the ropes. You’ll need to be patient, as they’re not always available and often have other tasks that they’re working on.

From my observations, you’ll really enjoy it. The people involved in these projects are all just humans. They want you to help. If you don’t want to beta-test, just let them know that you have some free time and let them know what skills you have in your toolbox. There’s always something you can do.

They may find a niche for you doing documentation, doing bug triage, answering support questions, keeping track of task-completion, or any number of things. Just contact the distro team, let them know you want to help, and they’ll find a use for you.

Closure:

You can make a meaningful difference. By taking part, you can make your favorite distro even better. It needn’t be a distro, it could just be a project you use and understand. The people writing ‘inxi’ can use your help, ‘Shutter’ too, or even ‘GIMP’ or ‘Blender’. Pick one and jump right in!

Seriously… Getting involved is easy! Even if it’s just you noticing and reporting a bug, you can meaningfully impact the software that you use every day. You can make a difference, and you can make it better.

The amount of time you donate is up to you. It needn’t be quite like the one to two hours I spend daily, it can be just a couple of hours a week. The choice is for you to make and it needs to fit your schedule.

As always, thanks for reading. Don’t forget that you can unblock ads, donate, write articles, and sign up for the newsletter. You already know that I appreciate the feedback. There will be a new article in just a couple of days.