It’s a weekend so today’s article will be short and easy, an article for when you want to find your last boot time in Linux. If you want to know when you last booted your computer, there are many ways to get that information. We’ll just cover one way…

We’ve covered a couple of ways to do this in the past. If you want, you can read the following article:

When Did I Last Reboot My Linux Box?

I wrote that article more than two years ago. It was one of my earliest articles. In that article, I covered a couple of different ways that you can find out when you last rebooted your Linux computer.

In that article, we covered commands like:

1 | last reboot |

There are some advanced commands you can use, so do read the previous article to learn more about how you can find your last reboot time.

In that article, I also mentioned that you could see how long your computer has been on since the last reboot with the uptime command. That’s simply done:

1 | uptime |

Speaking of the uptime command:

How To: Find Your Uptime In Linux

The Meaning Of “Load Average” On Linux?

Those articles might be of interest. This is a simple article, but it does allow you to read quite a bit more related content.

Find Your Last Boot Time In Linux:

You guessed it. We’ll be doing this in the terminal. That means you’ll need an open terminal. If you’re not sure how to do that, look in your application menu or press

For this article, we’ll be using the who command. You can check the man page with man who to learn more about the command. If you do that, you’ll learn that the who command is described as:

who – show who is logged on

That may not be as descriptive as it could be. If you just run the following command, you’ll be able to see everyone who is currently logged into your system. That’s just this command:

1 | who |

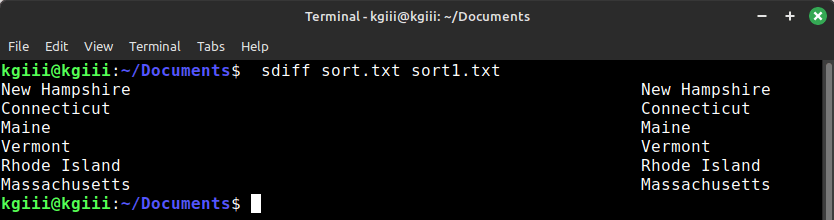

That simply tells you who is logged in. Your output might look a little like this:

1 2 3 | kgiii@kgiii:~$ who kgiii tty7 2023-09-29 14:53 (:0) kgiii tty3 2023-10-04 18:46 |

As you can see, I am logged in both on tty7 (the desktop) and tty3.

If you did check the man page, you’d have possibly seen the -b flag. That flag is described accurately:

-b, –boot

time of last system boot

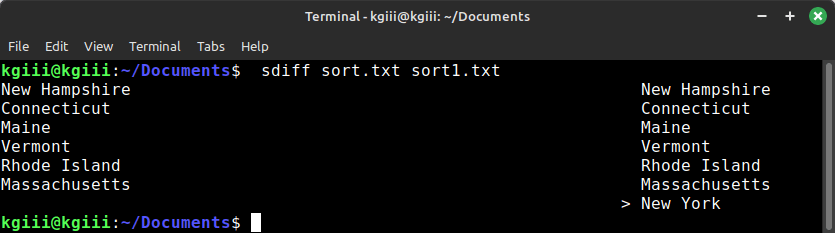

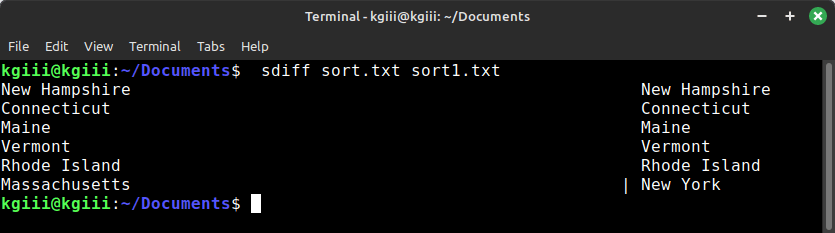

See? Now it should be obvious why I’ve chosen to write this article about how you can find your last boot time with the who command. The command is simply:

1 | who -b |

Which will output something similar to this:

1 2 | kgiii@kgiii:~$ who -b system boot 2023-09-29 14:52 |

See? That’s all you need to know if you want to find your last boot time! It’s not all that difficult to get started with the Linux terminal. This is a command any Linux user can learn. It’s also a pretty easy man page to decipher. So, that’d be good for new users as well!

Closure:

It’s a weekend and I’m lazy today. So, you have an easy article. It doesn’t have to be all that easy. I gave you plenty of links that you can (re)visit. Visiting those links will also show you how much the site has changed – specifically with how I write the articles. This particular article is a lot like how I wrote many of the articles, but I’ve been mixing it up quite a bit. I was just really in the mood for an easy article today, so you got this one about using the who command to show when you last rebooted your system.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.