Today’s article will teach you how to mount an .iso in Linux, a task undertaken seldom but worth knowing. This isn’t something I use often but it’s something you may want. It promises to be a quick and easy article, so read on!

I’m pretty sure the ‘unmount’ is incorrect English and that it’d be ‘dismount’ if you had mounted something like a horse or gym equipment. But, when I look around the web I see ‘unmount’ used with greater frequency. So, I’ll be saying ‘unmount’, even though that seems wrong.

Why would you want to mount an .iso? Well, there’s software that’s meant to be run from CD/DVD. You could burn your .iso to optical media or you can just mount the .iso and use it from there. Rather than wasting time burning the disk, you might just as well mount it.

You might want to verify that the image works before you burn a copy or upload it to share it. You might want to make edits to an .iso image and mounting the .iso will help with that, as you’d obviously unmount the image between changes.

So, you have a few reasons as to why you might want to mount an .iso. This article will explain how. It might not be a skill you need to day, but it’s one you may want eventually. We might as well get it written down now.

Mount An .iso In Linux:

This article requires an open terminal, like many other articles on this site. If you don’t know how to open the terminal, you can do so with your keyboard – just press

The first command you need to run is to set up the mount’s directory:

1 | sudo mkdir /mnt/iso |

With that done, you can navigate to the directory where your .iso is stored or just use the full path. Your command should look a little something like this:

1 | sudo mount -t iso9660 -o loop /path/to/file.iso /mnt/iso/ |

When you’ve done that, the .iso should be mounted and remain mounted until you unmount it or reboot. This is not a permanent mount, so you’ll not have any permanent changes to your system because of this. For permanency, you’d need fstab.

By the way, just cd /mnt/iso to navigate to your newly mounted iso and that should work just fine. If you want to unmount the .iso on your own, you’d just use this command:

1 | sudo umount /mnt/iso |

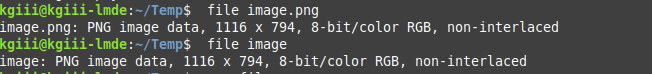

You can verify that you mounted and unmounted it with the lsblk. The output from that command should first show the .iso mounted and then show it when it’s unmounted.

Closure:

That’s about it. There’s not much more to say about how you mount an .iso in Linux. It’s a pretty simple activity and one easy to master. In my case, I just do it so infrequently that I never actually remember all the commands. So, it ended up in my notes – which means it turned into an article.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.