Today’s article is only going to apply to some of you, specifically those who use RHEL and want to remove unused kernels from RHEL. That’s a pretty narrow subset of people, but it’s worth knowing this information if you’re a RHEL user.

Red Hat is one of the oldest Linux distributions out there. Along the way, they’ve turned into an ‘enterprise’ (business class) distro. They’ve made some strange strategic decisions lately, but I’m not going to get into that in this article.

As an enterprise distro, it is not entirely free (as in cost in dollars). They are a distro that has a great deal of support for long periods. They’re meant to be stable and ideal for business use. You’re expected to pay for RHEL – sort of.

RHEL has a free version if you sign up as a developer. You can learn about the RHEL developer program at this link. I thought it was free for a few devices, but it looks like I might be wrong and that it may be more than that. From the linked page:

An entitlement to register 16 physical or virtual nodes running Red Hat Enterprise Linux.

So, that’s more than three – but you’re not going to get support. If you want to go this route, you’re expected to support yourself. Fortunately, RHEL has extensive documentation and your dev subscription will get you access to any of that documentation that’s behind a paywall. Or, at least that’s my experience.

I don’t do enough with RHEL!

Linux Kernels:

I’ve explained what the kernel is before. Linux is just the kernel. We add stuff to the kernel to make an operating system. We then add more stuff to make it a specialized operating system – such as a desktop operating system, like the readers of this site use.

Along the way, as you update and upgrade, you’ll add new kernels. These are not necessarily removed by default. They can take up quite a bit of space and you might be paying for that space (especially if you’re using RHEL as a server somewhere). So, removing the oldest kernels is just good housekeeping.

That’s all we’re doing in this article. I suppose it’d probably also work for CentOS but I don’t pay any attention to that distro these days. It’s not that I’m angry or annoyed with RHEL’s decisions, it’s that I only care for things with long-term support. I’m old and changes scare me!

We’re just going to clean up any old kernels, probably while keeping the 2 most recent kernels, to keep things nice and orderly. This isn’t something you technically have to do. You can keep all the kernels you want. But, if you want to remove unused kernels from RHEL this might be the article for you!

Remove Unused Kernels From RHEL:

Now, if you’re using RHEL as a server then you’re already connected via SSH (probably) and already have a terminal open. If you’re using RHEL as a desktop OS, you will need to open a terminal. You can just press

With your terminal open, you first need to install yum-utils. That’s nice and easy, just use this command:

1 | yum install yum-utils |

(You’ll need elevated permissions unless you’re logged in as root.)

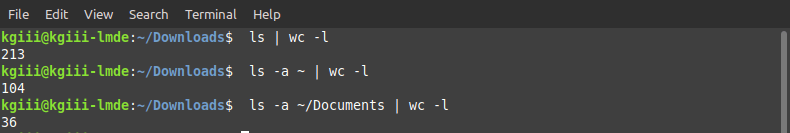

Next, run the following command to see how many kernels you have installed:

1 | rpm -q kernel |

If you have more than two kernels installed, you can run this command:

1 | package-cleanup --oldkernels --count=2 |

You can adjust that command if you’d like. That particular command will keep the kernel you are currently using and the previous kernel. (You can boot to older kernels via GRUB if you want. That article is actually about recovery mode on Ubuntu, but the pictures should clue you in until I write an article just for this purpose.)

If you use a --count= of 1 or 0, it will remove every kernel except the one in use, it will not remove the kernel that’s in use.

That’s all you have to do. There’s nothing more to it. The command will automatically remove older kernels at the level you decided. You can keep the most recent three kernels, four kernels, or however many kernels you want. It’s not terribly complex.

Closure:

I don’t do a whole lot of RHEL articles, but it’s nice to at least write one here and there. If you’ve got extra kernels, you now know how to remove unused kernels from RHEL. It’s a pretty easy task and something even a new user can handle. If you’re a new user, go for it! It won’t break anything – in and of itself. (I’d highly recommend keeping the current kernel and the most recent kernel, just in case.)

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.