Before making this site, I had a similar article that explained how to list installed applications in Linux, but it was only relevant to those that used distros with ‘dpkg’. This expanded article will explain how to generate a list of installed applications for multiple distros, in order to be more complete.

There are any number of reasons why you might want a list like this. Maybe it’s for compliance reasons, needing to know everything installed on the machine. Maybe it’s for making a manifest to establish a baseline for future installs. You could also just be curious, need a list for support questions, or want a list for backup purposes.

Whatever your reason, you can generate a list of installed applications fairly easily. You can also do a couple of other neat things that I’ll explain below.

Generate a List of Installed Applications:

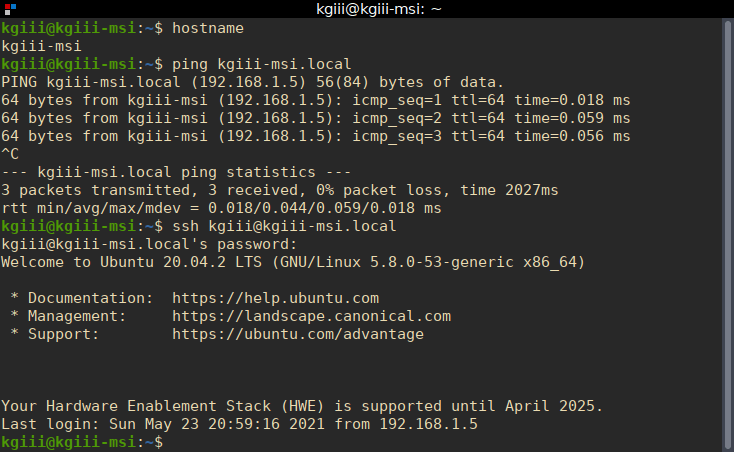

For all of these commands, you’ll want a terminal. You can probably open your default terminal by using your keyboard to press

The command you’ll use will vary depending on your distro. I’ve got a few of them covered below. In some cases, you may need elevated permissions, so a ‘sudo’ in the front of the commands should do the trick for you.

Debian (& dpkg using distros):

1 | dpkg -l |

If you’re using Ubuntu, or a distro with snaps, you can list those with:

1 | snap list |

If you’re using flatpak applications with any distro:

1 | flatpak list --app |

Arch (& Mandriva, etc.):

1 | pacman -Q |

RHEL (& Fedora, etc.):

1 | rpm -qa |

OpenSUSE (& derivatives):

1 | zypper se --installed-only |

Those are the major distros. There are smaller distros, independent distros, and they’ll have their own package management systems and ways to make a list of installed applications.

Bonus:

You can actually do a few things with this listing. Two immediately come to mind and I’ll share them.

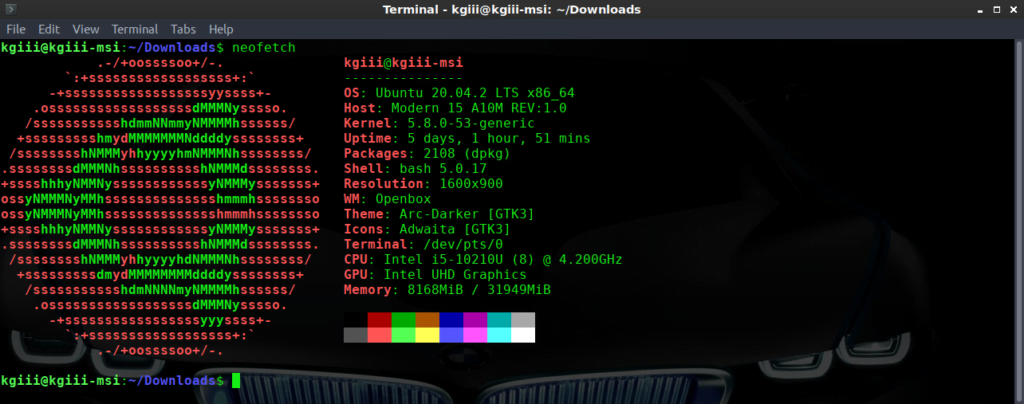

First, you can count them. At the end of each of these commands, you can pipe it and count the lines. It may not be a 100% accurate number, but it will be pretty close. (Some of the commands output more than just a list of installed applications.)

1 | | wc -l |

That’ll give you an output similar to:

1 2 | kgiii@kgiii-msi$ dpkg -l | wc -l 2134 |

You can also write the list of installed applications to a text file, to save for archiving or whatever. I like to make a list now and then and check against it when I do a new installation. Your reasons are your own, but here’s how:

1 | >> ~/Documents/installedapps.txt |

The .txt isn’t mandatory and you can write the file to anywhere you want, assuming you have the correct permissions. It’s your list, you can do anything you want with it!

Closure:

And, there you have it. You can now make a list of all applications that you’ve installed. You can even count the list, and you can write the list to a file for storage. If you want, you can generate a list of installed applications on one computer, generate a list of all applications on a second computer, and then use ‘diff’ to see what the differences between them are. There’s all sorts of things you can do with this list.

As always, thanks for reading. Your reading and feedback help me stay motivated. My goal is to keep up this publication rate for a year, though we’ll see where we are when that year ends. I have enough notes for that, and more.

If you’d like to contribute, you can unblock ads, you can sign up for the newsletter, you can write an article, you can donate, and you can register for the site to regularly contribute. You can also comment, vote for articles you do like, and share this site/page with others via social media! You can even buy inexpensive Linux hosting! Alternatively, you can even just enjoy the articles. It’s all good!