In today’s article, we’re going to learn how you can go to a specific line in Nano. It’ll be an easy article, perhaps even a fairly brief article. There are a just a couple of ways to cover, so it won’t take all that much time or space.

Often, when things like scripts throw an error, they’ll tell you on which line number the error happened. There are often hundreds or thousands of lines in complicated files and navigating to the correct line number is tedious, prone to error.

You can be pressing the down arrow for quite a while! So, why not note the line number where the error occurred and open the file at that specific line? It’s perfectly good sense! It’s such good sense that I figured I’d write an article about it.

You all know that I’m a Nano fan. You can read the ‘big’ Nano article here. If that’s not enough, this link is to a search for Nano across the entire site. There are nearly 30 articles that use Nano in them. I really am quite a fan.

Why am I a fan? Well, the first link will probably tell you that, but I like it because it’s simple. Nano’s starting to be fairly universal. It’s light and that’s why I like it – it’s only meant for quick text file edits.

Nano’s not really the right tool for writing a book, nor would I want to use it to write large scripts or for programming. For what it is, it’s great. If it’s not great, odds are good that you’re not using it as the tool it is. Sure, it’ll work for other things, but it excels at being what it is – a quick text editor in the terminal.

Go To A Specific Line In Nano:

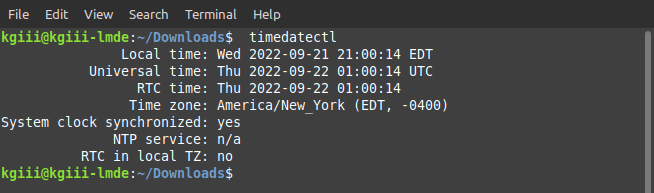

Nano is a terminal-based tool. So, you obviously need to have an open terminal. If you don’t know how to open the terminal, you can do so with your keyboard – just press

With your terminal open, let’s show you how to go to a specific line in Nano. It’s pretty easy, and we’re going to use a file most users will have. If you don’t have a ~/.bash_history file, you can use any plain text file you want.

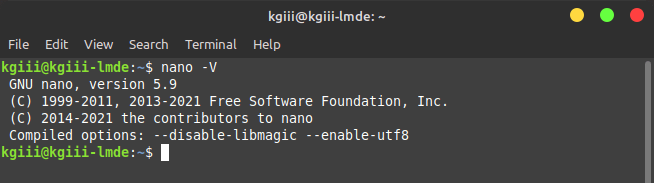

I suppose we should first make sure that you have Nano installed. To check, you can just look for the version. That’s done with:

1 | nano -V |

Your output should look something like:

If Nano isn’t installed, and you’re using any mainstream distro, it’s certainly in your default repositories. You can install it like you would any other piece of software in the repositories.

Now, there are two ways to open and go to a specific line in Nano. The first is probably the easiest. Using our ~/.bash_history as an example, the command looks like this:

1 | nano +25 ~/.bash_history |

Where you see the +25 flag, that’s the place where you specify the line number to start with when you open Nano. You can use any number you want, provided there are that many lines in the file you’re intending to edit.

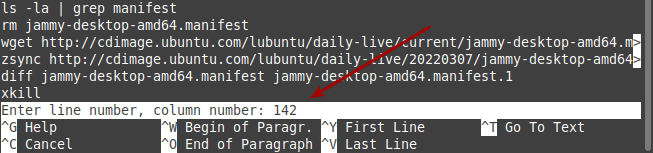

The next way is also easy. Using your keyboard, press

So, now you have two ways to go to a specific line in Nano. I told you that it was going to be easy! Nano is awesome.

Closure:

There’s another article! It’s on one of my favorite subjects – Nano. Now you’ve learned how to go to a specific line in Nano, which is a pretty handy trick to have in your toolbox. It can save you all sorts of time, and not just time scrolling. It means you aren’t paying attention to the rest of the fluff and you can concentrate better, or so it seems to me. For what it is, Nano is my favorite plain text editor and it’s remarkably useful at times.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.