In today’s article, we’re going to learn another way to find the binary for a specific command. This won’t be a very difficult article. It’s an article that will be easy enough for even new Linux users to follow. So, if you want to find the binary for a specific command, read on!

You’ll find some similarities between today’s command and the ‘which’ command, which we used in this article:

Well, we’ll use the ‘whereis’ command in this article. The man pages for the ‘whereis’ command describe it ‘whereis’ thusly:

whereis – locate the binary, source, and manual page files for a command

You may recognize the command, as we’ve used it to find the man pages for a specific command. In that article, we discussed the possibility of using the ‘whereis’ command to do just this, but I feel it deserves its own article. The first article merely mentions the possibility, so an article specifically discussing this command’s use like this makes perfectly good sense to me.

So, let’s learn another way to…

find the binary For A Specific Command:

As you might have guessed, the ‘whereis’ command is a command used in the terminal. As such, you’ll need an open terminal. Just press

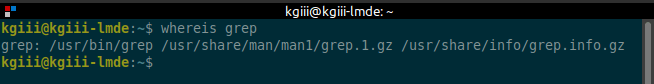

Now, with your terminal now open, you can try to find the binary for a specific command. Let’s say you want to find the binary for ‘grep’. Then the command would look like this:

1 | whereis grep |

The output of which would look a whole lot like this:

The extra fields are where the man page and info pages are located, and the first field is the path to the binary in question. So, if you want to find the binary file for Firefox, the pattern is:

1 | whereis <application_name> |

So, for Firefox specifically, you’d run:

1 | whereis firefox |

However, if you just want to find the binary for the specific command, you’d use the -b flag. That’s all you need to do in this case. It looks like this:

1 | whereis -b firefox |

And that will output just the binary file’s location without the additional fields of man pages and info pages. See? It’s pretty easy after all.

Closure:

Well, there’s another article. This time around, we’ve learned another way to find the binary for a specific command. It’s another article in a long list of articles, indeed a growing list of articles. So, well, there’s that… Which is nice…

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.