Today’s article is going to teach you how to find out which shell you’re using. Knowing which shell you’re using is important if you’re using an unfamiliar system. Most of the time, it’s something you’d already know, but once in a while you might need to find out which shell you’re using.

As you’re visiting this site, it’s fairly safe to assume you’re using Linux (or at least interested in Linux). In that case, you’re quite likely using Bash. Bash is the most common, from my observations.

If you’re curious, Bash is a replacement for Bourne Shell – and is ‘Bourne Again SHell’. It has existed, thanks to the Brian Fox and the GNU Project, since the late eighties. It’s pretty ubiquitous, pretty stable, and pretty feature complete.

While Bash is the most common, it’s certainly not alone in the field of shell options. There are other shells, from ZSH to Fish, or from Dash to Nushell. In some distros, you might find one of them installed by default, but it’s usually going to be Bash.

So, odds are pretty good that you will already know if you’re using something other than Bash. After all, you’d likely have been the person who installed the alternative. Still, there are a couple of commands you can use when you want to figure out which shell you’re using, for when you do need to know.

Find Out Which Shell You’re Using:

This article requires an open terminal, like many other articles on this site. If you don’t know how to open the terminal, you can do so with your keyboard – just press

On the off-chance that you don’t know what a shell is, Wikipedia describes the shell as:

A Unix shell is a command-line interpreter or shell that provides a command line user interface for Unix-like operating systems. The shell is both an interactive command language and a scripting language, and is used by the operating system to control the execution of the system using shell scripts.

And now, with your terminal emulator open, let’s go about finding out which shell you’re using.

The first command you can try would be:

1 | echo $SHELL |

You can also use the echo command in a different way. It’s even a bit more clear with this command:

1 | echo $0 |

You can also use ‘ps’ which takes snapshots of current processes:

1 | ps -p $$ |

There are certainly other ways to find out which shell you’re using, but those are a few ways that are easy enough. If you have other ways, please feel free to leave them as a comment.

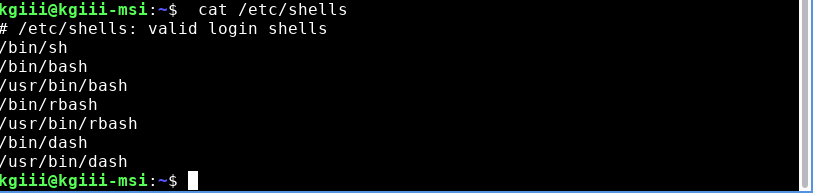

Oh, and here’s a bonus… If you want to see which shells are installed on your system, you can use the following command:

1 | cat /etc/shells |

The output of this would look similar to this:

As I said, that’ll let you know which shells you have installed. In a future article, we might discuss how to change your default shell – but that’s something I seldom bother with these days. Bash works and works well.

Closure:

Yup… There it is! Another article. Now that the year is up, I’m not sure what to look forward to as a goal. I highly doubt I’ll make it a full two years, but it could happen. We shall see…

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.