Today’s article is one I could have already written and it’s about how to prevent brute-force SSH attacks with fail2ban. The reason I haven’t written it yet is because it either has too much substance or too little substance. I think I can strike a middle-of-the-road here and write an article with just enough substance.

See, and we’ll get to this later in the article, most folks won’t need to do a whole lot more than just install it. You can configure it a great deal, but the defaults are just fine for most people. On top of that, you can even make fail2ban send you email reports but we won’t be covering that in this article. Instead, we’ll largely have directions for installing fail2ban so that you can “prevent” brute-force attacks via SSH. I put the “prevent” in quotes because a diligent attacker could time things, use varied IP addresses, and try brute forcing your login credentials.

I think we need to start at the beginning.

What is SSH:

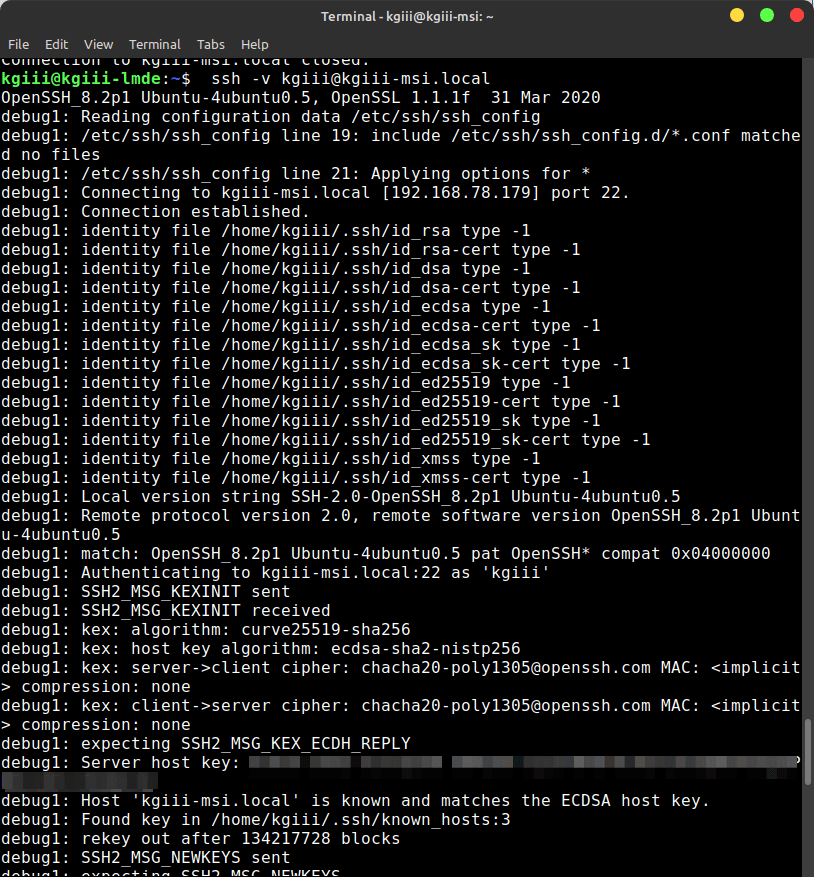

SSH stands for “Secure Shell” and is a tool to connect to a server remotely. If you check the man page for SSH it is defined as:

ssh — OpenSSH remote login client

This allows you to connect two computers over the terminal. It also comes with SFTP so that you can securely transfer files. You can do a whole lot more with SSH, including forwarding the graphical environment.

Here are a few SSH articles:

Install SSH to Remotely Control Your Linux Computers

Check Your SSH Server Configuration

Show Failed SSH Login Attempts

Then, there are a whole lot more SSH articles. I love SSH, so there have been quite a few articles on the subject. It’s a tool that I use quite often. I encourage familiarity with SSH as it’s sometimes a useful tool to effect a repair on a computer that is otherwise unresponsive to local inputs.

Servers are typically managed with SSH. As you can imagine, servers are a juicy target for malicious people. This means that SSH is a means with which malicious people will use to attack servers. One of the ways they do that is with ‘brute-force’.

What is Brute-Force:

There are many ways that one can try brute-forcing something. The name is as it implies. Rather than knowing the login credentials, they try to brute force them. That means they’ll try one combination of username and password and then keep trying various combinations until they eventually crack the system and figure out the login information.

That is the goal. Their goal is to find the login credentials. Instead of finesse, they use brute force.

This can include a dictionary attack. This can include a progressive attack where they start at the letter a, then try aa, then try aaa, etc. until they find the login credentials. They may also have a list of commonly used usernames and passwords and will systemically work their way through this until they find their way in.

This is one of many attacks and a modern computer can make many attempts in a short amount of time. Add to this modern bandwidth speeds and you can get thousands of attacks in just a short amount of time. It goes even faster if they know one part of the data, such as the username of a privileged account.

Enter fail2ban:

If you’re using a major distro, you have fail2ban available, one way or another. It’s usually easily installed and in your default repositories. When you do install it, you can check the man page. However, fail2ban is described as:

fail2ban – a set of server and client programs to limit brute force authentication attempts.

So, as you can see, fail2ban is the correct tool for the job. After all, and as the headline suggests, we’re trying to prevent brute-force SSH attacks with fail2ban.

Installing fail2ban:

We’ll be using a terminal to install fail2ban. You may also need to remotely connect to the server on which you want to install fail2ban. That too will require a terminal (or some SSH application like PuTTY). Simply press

With your terminal now open, we can install fail2ban.

Debian/Ubuntu/etc:

1 | sudo apt install fail2ban |

RHEL/CentOS/etc:

1 2 | sudo yum install epel-release -y sudo yum install fail2ban |

Fedora with dnf:

1 | dnf install fail2ban |

I believe those are correct. That’s what is in my notes. If they’re not correct, please leave a comment and I’ll update the article. Other distros will have fail2ban available, just search your default repositories and you’ll likely find fail2ban available for installation.

Using fail2ban:

Now that you’ve installed fail2ban, you’re pretty much done. The default configuration is pretty much all you need – but you can customize it. There are a bunch of options available, so you can configure fail2ban in many ways. There are so many ways that we won’t be covering them. They’re reasonably obvious.

Once installed, fail2ban should start automatically. If it doesn’t, run this command to start it:

1 | sudo systemctl start fail2ban |

Next, we’ll make sure to enable fail2ban to start at boot time. That’s this command:

1 | sudo systemctl enable fail2ban |

I assume that you’ll want to at least examine the configuration files and I’ll get you started with that. The first thing you want to do is cd to the right directory.

1 | cd /etc/fail2ban/ |

If you run ls you’ll see that there’s a file called jail.conf and you do not want to edit this file itself. Instead, fail2ban will look for configurations in a file called jail.local first. To make that file, you run the following command:

sudo cp jail.conf jail.localNext, you might want to make a backup of that jail.local file.

1 | sudo cp jail.local jail.local.backup |

You can now use Nano to edit your fail2ban configurations:

1 | sudo nano jail.local |

As you can now see, there are a bunch of options available. They’re far too many to explain here but they’re fairly well described. If any of the options confuse you, you can get help on the man page (man fail2ban ).

After you’ve set fail2ban’s configuration files the way you want them, you’ll need to restart the service for the changes to take effect. That’s done like this:

1 | sudo systemctl restart fail2ban |

If you screw up the configuration, just remove the jail.local with this command:

1 | sudo rm jail.local |

Then restore from your backup like this:

1 | sudo cp jail.local.backup jail.local |

Then, of course, restart the service with this command:

1 | sudo systemctl restart fail2ban |

There are a lot of options with this application. You can explore them at your leisure, though I find the defaults to be adequate for most of my needs. As mentioned above, you can install sendmail and have the system send you notification emails. There are many other options as well.

Closure:

Like I said in the beginning, there’s a lot of substance with fail2ban. There’s a lot to it. If I added more to the article, it’d end up quite long. I may write a bit more about this application, but I don’t want to end up with a 2500-word article that will make your eyes gloss over. That doesn’t do me any good and it doesn’t do most people any good. Most folks are going to be fine with the basics before they explore the configuration options on their own.

If you do have a server (or even a personal computer) that’s running SSH, it’s worth your time to install fail2ban. If there’s any chance that someone can try to brute-force your system, they will.

Some bots crawl the ‘net looking for servers that respond on the default SSH ports. They can and will find you. You can also change the port SSH uses for some added obscurity (but remember that obscurity isn’t really security). So, it’s a good idea to prevent brute-force SSH attacks with fail2ban. Yes, it’s a good idea even for us ‘little guys’ who aren’t running servers with valuable information on them.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.