Today’s article will be a fun one, where we figure out how to get some system information with Archey. It’s a mostly unnecessary article and Archey is definitely replicating work done elsewhere, but it’ll be fun!

Well, I think it’ll be fun…

I suppose you can decide that for yourself as you read the article. If you want to get some system information with Archey, read on (and maybe have fun)!

As regular readers might know, I’ve covered a variety of *fetch articles.

How To: Display System Information With screenFetch

Screenfetch vs. Neofetch, You Decide!

Show RAM Information With Ramfetch

Get Some Prettified CPU Information in Your Terminal With ‘CPUFETCH’

In fact, the ‘Screenfetch vs. Neofetch’ article is oddly one of the most searched articles on the site, at least from Google’s traffic.

Anyhow, Archey is like those (but written in Python, if that matters). If I understand correctly, it was Archey4 – a maintained fork of Archey. The original Archey project ceased development and now this project is just called Archey as it is no longer a fork but is the actual project.

I think I’m understanding that properly. If I’m not, hopefully, someone chimes in and lets me know the full story. Often my articles are visited by project leaders, so maybe that’ll happen in this instance and someone will set the story straight.

Either way, it doesn’t matter much – but it does explain why I’m simply referring to the project as ‘Archey’. If you check the man page, you’ll learn that Archey describes itself like:

A simple system information tool written in Python

Got it? Good! Let’s get started getting some system information with Archey!

Let’s Get System Information With Archey:

So, the first thing you’re going to need is a copy of Archey. That’s easily accomplished if you want .deb or .rpm. There are some odds that you’ll find it’s already in your repositories (like Arch or BSD). You can also use “pip” (Python packages from PyPI) to install Archey. There’s even a ‘homebrew’ version for Mac users.

Otherwise, if none of those will work for you, you might find you need the source code to build and install Archey.

This link should take you to the current release:

https://github.com/HorlogeSkynet/archey4/releases/latest

From there you can install Archey. Due to the huge variety of installation methods, I’m just going to tell you to follow the directions to install Archey. If you can’t get it installed, you can always ask for help and someone will hopefully get you sorted.

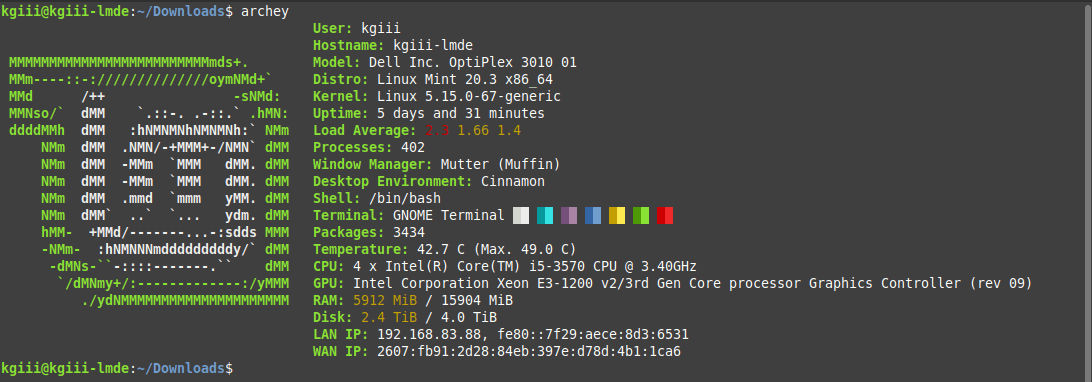

Once you have Archy installed, you can start getting system information with Archey. You just run the archey command and it’ll spit out something like this:

As you can see, Archey’s output is fairly normal. It likely reminds you of things we’ve already covered in earlier articles. That’s okay – it should remind you of things like Screenfetch and Neofetch.

Just like some of the other previously covered *fetch applications, you can take a screenshot automatically. After all, the goal of these applications is to give you some information that si easily captured as a screenshot so that you can show it off to your forum buddies.

However, possibly because I have Flameshot installed (which seems to have taken over the ‘screenshot’ command that Archey uses), I am unable to actually verify the screenshot bit. I dutifully took the screenshot with Shutter. But, the -s flag should work for other people. I tried a few times with Archey but got conflicting errors. Someone smarter than I probably have this sorted out.

I’m not going to go uninstalling stuff just to demonstrate it. If it doesn’t work for you, file a bug at the above-linked GitHub site. Also, you have some additional options with Archey. There’s nothing too fancy, but be sure to check the man page (by using man archey) to learn more about the application.

Closure:

There you have it, you have another article. This article covers how to get system information with Archey. It’s an easy and, likely, familiar task. If you’ve followed along, you’ve learned all sorts of ways to get system information.

Do you really need Archey? No, probably not… I figured I’d cover it because my site shows up in some Archey queries. If people are looking for it, it might as well be here. That’s my line of thinking, at any rate.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.