Have you ever wanted to use your Linux computer as a wireless hotspot? It’s actually pretty easy. Today’s article will get you started and it really isn’t all that difficult. We will actually be cribbing a bit of this article from the software’s homepage, but while some more, rather important, information added.

For many years, I used my own router that I had configured on my own hardware. It was built on Linux. The preceding version actually ran on BSD, but that’s not important for a site called Linux-Tips. Today, you can get a NUC or Pi for dirt cheap and so making a new router is back on my list of things to do. In other words, it’s a fun project that won’t take a lot of money to get into.

All of the varied software and hardware components are already there to make your own router, but I want to enable wireless connectivity. a wireless hotspot, and that’s what we’re going to look at today. The tool we’re going to use is called ‘linux-wifi-hotspot‘ That’s is a great tool, complete with GUI if wanted, written by lakinduakash. It has only been around for a few years, but it’s spoken of very highly – and it just works and works well.

At least it worked the last time I used it. This article is from the old site and I’m just moving it to this site. I actually haven’t bothered much with my own router for the past year or so. So, this information is a bit dated.

Turn Your Ubuntu Into A Wireless Hotspot:

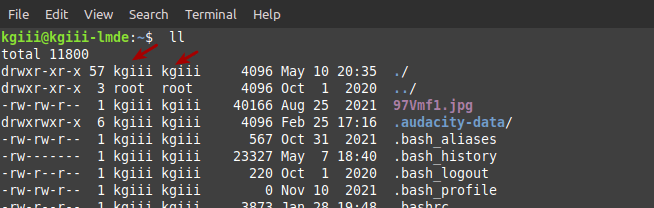

This article requires an open terminal, like many other articles on this site. If you don’t know how to open the terminal, you can do so with your keyboard – just press

The software is easy enough to install. If you’re using Debian/Ubuntu, just add the PPA and install the software. To add the PPA, you just run:

1 | sudo add-apt-repository ppa:lakinduakash/lwh |

On a modern Ubuntu, you shouldn’t need to do this, but you might want to go ahead and run a quick update with:

1 | sudo apt update |

Then you can install the software, starting to get your system into a workable wireless hotspot. To do that, it’s just:

1 | sudo apt install linux-wifi-hotspot |

If you want, you can visit the link above (in the preamble), click on releases, and download the .deb file for the current release and just install it with gdebi. In this case, I’d suggest installing with the PPA – just to make sure

Then, you can go ahead and start it. You can also go ahead and make it start at boot, which would be prudent if you intended to use this to make your own router. It’s really self-explanatory and without specific questions for using it, I’m just going to refer you to the man page and the information at the project page.

Caveats:

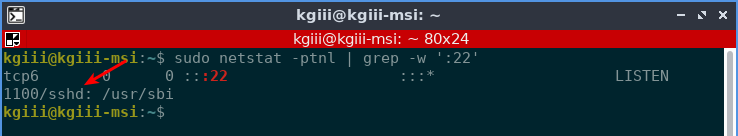

But, before you can even do all of this, you need to know that your wireless adapter actually supports doing this. To find out, you need to know if your wireless adapter supports “AP” mode. AP obviously meaning ‘Access Point’.

To check this, you need to run the following command:

1 | iw list | grep AP |

The project page is noticeably silent with this, but it’s a necessary step. See, you need to know if your hardware actually supports it before you even bother trying. Come to think of it, I probably should have put this closer to the top of the page! Ah well…

Anyhow, the output should contain one or both of the following lines:

Device supports AP scan.

And/Or:

Driver supports full state transitions for AP/GO clients.

So long as you see one or both of those, you should be all set to proceed. If you don’t see either of them, there’s no software solution and you’ll need to get hardware that supports AP mode. In many cases, that’ll mean doing a bunch of research and may even mean contacting the vendor or OEM.

Nobody appears to have compiled a list of hardware that supports AP mode and I don’t think I’ve ever bought wireless adapters that explicitly stated they do on the box. As near as I can tell, more modern adapters support it just fine, so you’ll probably be alright. Online specs are more thorough than what’s printed on the outside of the box, so maybe searching is okay.

Closure:

Alright, there’s your article for the day. I have no idea if you want to make a wireless hotspot for your Linux box, but now you know how. It’s pretty self-explanatory, and you shouldn’t have any questions. If you do, you know where to find me – or to find others who can help you – at Linux.org.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.