In this article, we’ll go hunting for rootkits with a tool known as ‘rkhunter‘. It’s relatively easy to use rkhunter and this article will show you how. Don’t worry, it’s not all that complicated. You can do it.

Recommended reading: What You Need to Know About Linux Rootkits

So, what is a rootkit? Well, for the purposes of this exercise, a rootkit is malware that hides itself while allowing privileged access to the system. In other words, it’s the kit that allows an unauthorized person to use the system with root privileges. The word ‘malware‘ refers to software that would do you or your system harm.

A rootkit is one of many types of malware, like viruses and trojans, and Linux isn’t entirely immune to such. If you give an application privileges, it can and will use those privileges. That’s true for software you want and software you don’t want.

Malware exists for Linux! Know what you’re installing before you install it, and get your software from legitimate sources! Linux has some security advantages, and your actions can easily nullify those advantages. If you give something the permissions necessary to make it executable, it can be executed – even if it’s malware.

The rkhunter application is a software tool that will help you check your system for rootkits and some other exploits. It doesn’t help you remove them, it only helps you identify them.

If you’re curious, rkhunter describes itself as:

rkhunter is a shell script which carries out various checks on the local system to try and detect known rootkits and malware. It also performs checks to see if commands have been modified, if the system startup files have been modified, and various checks on the network interfaces, including checks for listening applications.

Let’s put it to use!

Hunt Rootkits With ‘rkhunter’:

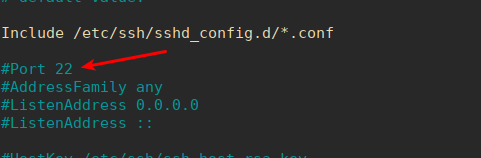

In order to use rkhunter, you have to install it. It’s possibly in your default repos and your package manager is ready to install it. If not, you can grab a copy from their repository and build it. Those using Debian or the likes, can just install it with:

1 | sudo apt install rkhunter |

You can adjust that for your distro to see if it’s available. If it’s a mainstream distro, it’s probably available. Once installed, you start the scan with:

1 | sudo rkhunter --check |

This command (there are others, jcheck man rkhunter) will be interactive. You need to sit there to press

After checking the warnings, see the log for more information. Read the log every time – that’s where most of the output is stored. Read the log with:

1 | sudo cat /var/log/rkhunter.log |

Now it’s up to you. You need to process that information. You may see output such as this:

1 2 3 | [18:41:13] Rootkit checks... [18:41:13] Rootkits checked : 477 [18:41:13] Possible rootkits: 8 |

That doesn’t mean I have 8 rootkits, it means I need to check the logs further to see what it’s calling a potential rootkit. In this case, one of the signs of a rootkit is a process that takes up a lot of RAM. Well, my browser is taking up a bunch of RAM and that’s one of the things it is warning me about.

When I say it’s up to you, it’s really up to you. You have to read the report and the logs to understand what is going on. DO NOT PANIC! The warnings can look scary – but they’re often just warnings. Read the logs thoroughly and understand what you’re reading before you do anything drastic!

Closure:

And there you have it! Another article in the books and this one about security. If you think you have a rootkit, feel free to leave a comment, but rkhunter tends to be a little trigger-happy with the warnings.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.