It is possible to use sudo without a password. Doing so is probably a pretty bad idea for most people, but it can be done. Password-less sudo is an option that you have, but it’s one heck of a security risk.

I have pretty good physical security and the risks of someone physically accessing my devices are pretty minimal. There’s no neighbors that can access my WiFi, or anything like that. Because of this, I can, and sometimes do, set up my computers so that I don’t need to use a password when I use sudo.

I feel like I need to make this clear:

If you set it up to use sudo without a password, you’re removing a key security element. If you can use sudo without a password, so can’t someone who’d be doing so with malice aforethought. It’d be even more risky if you did this on a laptop that might get misplaced or stolen.

In short: DO NOT DO THIS (without considering the security implications).

By the way, if you don’t know what sudo is, it stands for “superuser do”. It’s what you use to temporarily elevate your permissions, to read, write, or execute administrative (or otherwise restricted) files. Basically, it turns you into an omnipotent administrator.

Again, be careful before doing this. If it makes you an omnipotent user, it makes anyone that can access the device an omnipotent user. You have been warned. If you’re comfortable with your physical security, this is an option. It’s an option you should consider only with care and diligence.

SUDO Without A Password:

See Also: Generate Complex Passwords

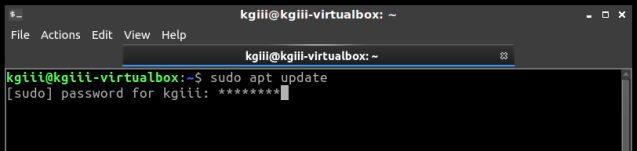

Like so many things, this too starts in the terminal. As always, you can open your terminal with your keyboard, just press

1 | sudo nano /etc/sudoers |

Arrow button yourself down to the bottom and add the following line:

1 | <your_username> ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD:ALL |

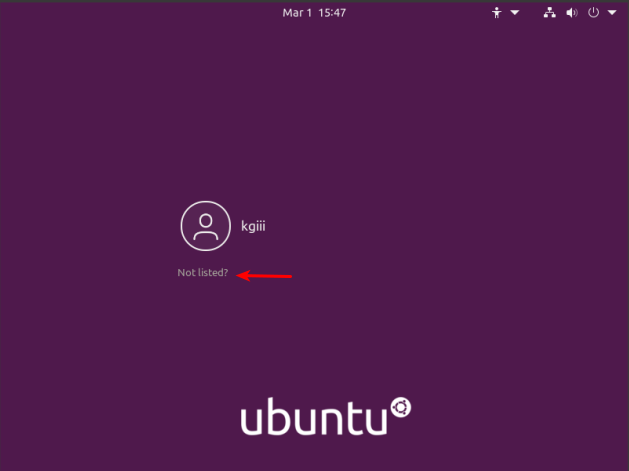

Where it says “<your_username>” you change it to your username – without the brackets. So, if your username were the same as mine, you’d make a line that looks like:

1 | kgiii ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD:ALL |

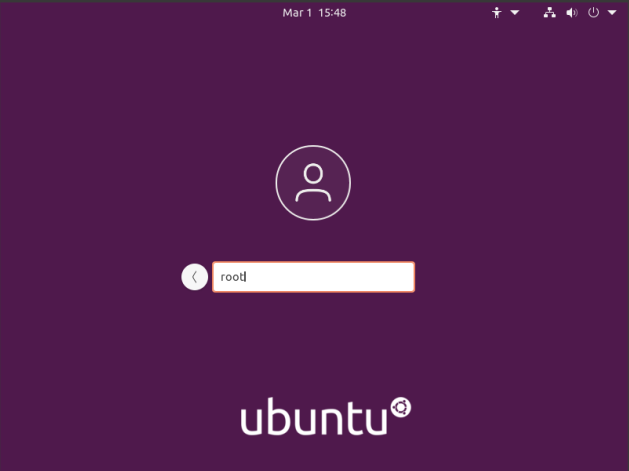

The ‘kgiii’ is lowercase, and your username will be lowercase. If, for some reason, you don’t actually know your username, you can find it with:

1 | whoami |

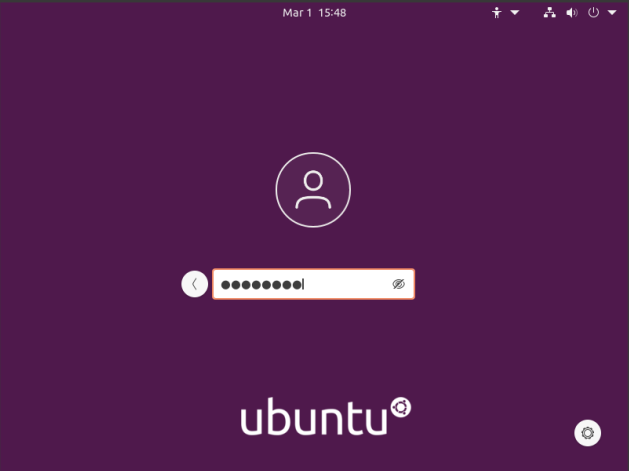

Anyhow, after you’ve added that line, you can save the file. As we’re using nano, you save it by pressing

That should get you sorted and you should now be able to use sudo without a password. If you are aware of the security implications, this may just be something you want to do. On the other hand, it’s not exactly taxing to type your password.

Closure:

And, once again, you have another article! I’ve reached the point where I have a small buffer. I could be offline for a few days and articles will still publish themselves. I’m hoping to get even further ahead, so we shall see how it goes.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.