Today’s article will be a nice basic article, where we discuss how to update Ubuntu in the terminal. It seems like a fine article to write and one that not everyone will be versed in. There are lots of folks who don’t use the terminal for much of anything. Then, there are people like me who use the terminal for all sorts of stuff.

If you know how to update Ubuntu in the terminal, this really won’t be a very interesting article. We’ll just be covering the basics and I’ll explain how I do it. You’ll see that I tend to throw caution to the wind and just blindly hope for the best. This strategy is fine for me, ’cause I can fix pretty much anything. (I can fix pretty much anything because I’ve broken pretty much everything.)

Of course, this article applies to Debian. This article applies to Linux Mint. This article should apply to anything that uses apt as the package manager. So, if your distro is related to Debian then this will probably work just fine for you.

Well, there’s no reason to make the intro any longer… I think I’ve covered all that you need to know to get started.

Update Ubuntu In The Terminal:

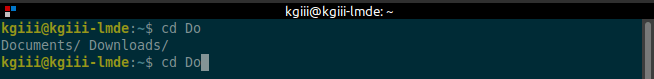

As you can guess, we need an open terminal if we’re going to update Ubuntu in the terminal. That only stands to reason… Press

With your terminal now open, let’s update the list of software that’s available. Let’s see what software can be updated. To do that, you just run:

1 | sudo apt update |

That will tell you the software that’s available to update. You can see what those updates are with the following command:

1 | sudo apt list --upgradable |

You can then upgrade those applications one by one if you want to. Some cautious people do this. Some businesses do this – and do this to a staging environment to test – ’cause they need to keep things running. If you want to upgrade just a single package, try this:

1 | sudo apt --only-upgrade install <package_name> |

Now, most folks are probably going to want to upgrade all the software that has new versions. They get it easy, they just type:

1 | sudo apt upgrade |

This will give you the chance to see everything that’s going to be upgraded and the chance to decline or agree. Me? I automatically agree. You might want to be more cautious, but I like running the command closer to this:

1 | sudo apt upgrade -y |

That automatically says yes that I’d like to upgrade all the things. After all, even if stuff were to break, I’d have had to have upgraded to find it anyhow.

I go a step further and just tie the two commands together. The command I run would look closer to this:

1 | sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade -y |

That will find all the available upgrades and install them automatically, that is without any further input from me. I’ve done this for years and it hasn’t been a problem or any more of a problem any other method would cause me. So, in short, that works for me.

Closure:

I don’t know that you wanted to learn how to update Ubuntu in the terminal, but that’s today’s lesson. It’s not very complicated. I could keep going, as my actually command also includes the ‘clean’ option. I use an alias to tie it all together, rather than typing it out each time. There are also similar commands you can use for other distros with different package managers.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.