Today’s article will be fairly simple, where we learn a couple of ways how to show your network interfaces. It won’t be a very long article, nor will it be all that complicated. Like almost always, today’s article will involve the terminal. So, if you want to learn how to show your network interfaces, read on!

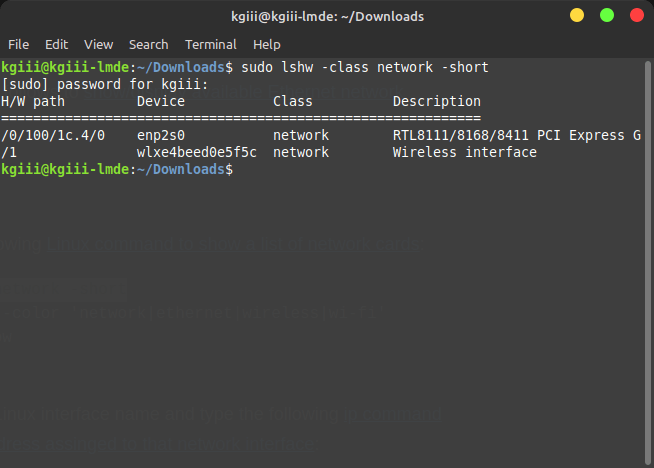

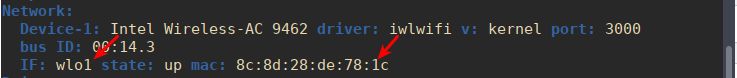

A network interface is what’s used to connect your computer to a network. Depending on your configuration, you may have both real and virtual network interfaces. The real network interfaces will be things like your ethernet (the wired connection to the network) and a wireless device (a radio-controlled network interface).

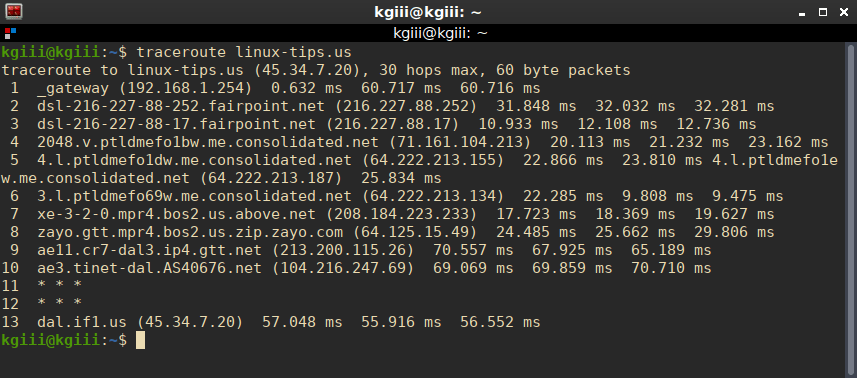

There are times when you’ll want to know your network interface, be it for debugging or monitoring. For example, you’ll probably want to know about your network interfaces if you’re playing around with VNStat.

We’ve probably touched on this subject in a few articles. However, we might as well have an article specifically answering the question of how to show your network interfaces. Well, then, that’s what this article will cover.

Show Your Network Interfaces:

As mentioned in the intro, we’re going to be using the terminal. If you’re a regular reader, you’re probably used to it and a little tired of the same old text. Not all my readers are going to be as proficient, so they should know that they can just press

With your terminal now open, your next step mostly depends on your chosen distro and the age of the default installed tools. If you’re using an older distro, you can go with this command:

1 | ifconfig -a |

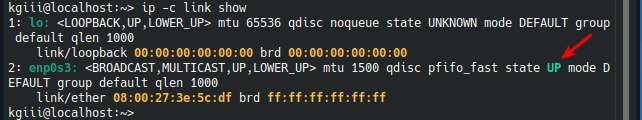

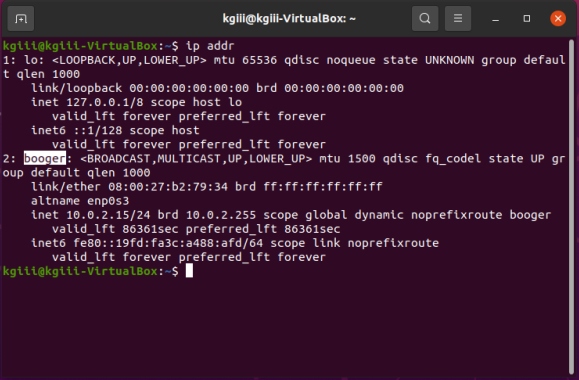

If you’re using a distro with more current tools, you will likely find that ‘ifconfig’ has been deprecated, that is no longer current and in use. For you folks, you’ll need a slightly longer command:

1 | ip link show |

So, if you want to show your network interfaces, one of those two commands will likely get you there. You should check the information carefully, to make sure you’re using the correct information, such as when you want to use a network interface name for another command.

Closure:

There you have it… You have another article! This time, we’ve decided to spend some time learning how to show your network interfaces. It’s nothing complicated, but it’s still useful information. It is indeed a fairly short and simple article, but that means newer users can follow along – which is a good thing. I’m sure there are other ways to gather this information, but one of those two commands should do the trick!

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.