Today, I’m going to show you how to check your SSH server configuration. It’s a simple process, but not one many people seem to know about. It’s also a pretty handy tool if you’re having SSH issues. Once again, this one isn’t all that complicated, I think… Read on!

So, why would you want to check your SSH server configuration?

Your SSH server might not be working. You may have made some changes and want to test it before moving it to production. An upgrade to the SSH application may have made some of the options different or even removed the options entirely.

There are all sorts of reasons why you’d want to check your SSH server configuration. Those are just a few of them. Not only will the article show you how to check your SSH configuration files – it’ll show you how to test alternative configurations. So, you can test your changes before making them – potentially saving you a physical trip to the server.

Check Your SSH Server Configuration:

This article requires an open terminal, like many other articles on this site. If you don’t know how to open the terminal, you can do so with your keyboard – just press

By the way, I would test/learn this on a local system. You’re potentially going to break things. In fact, let’s start by breaking them! Well, let’s create a backup first, and then we’ll break stuff.

1 | sudo cp /etc/ssh/sshd_config /etc/ssh/sshd_config.bak |

Okay. Now let’s break something! Run this command:

1 | sudo nano /etc/ssh/sshd_config |

Find a line that has a command and doesn’t start with a #. You can also remove the # from an option and it’ll be work. Find a one line option that has a “no” option field and change it to “oh_no” *sans quotes, though that probably won’t matter) and then save the file.

(Also, to save the file in nano, press

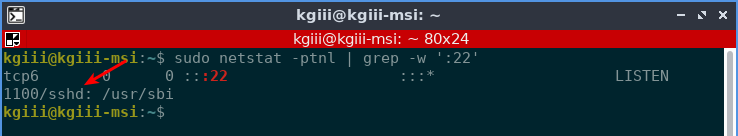

Now, let’s check that SSH server configuration with the following command:

1 | sudo sshd -t |

If things go according to plan, it will tell you that you have an error. On top of that, it will tell you on which line you have the error. If it doesn’t throw an error, it means your configuration is fine – or that you may need to restart your SSH service for it to see the new configuration.

If you do somehow need to restart SSH server (you shouldn’t have to), restart it with the following command:

1 | sudo systemctl restart ssh |

Run the command again and that should definitely show the error, which you can easily fix by simply undoing what you did in the steps above and saving it. You almost certainly shouldn’t need to restart SSH to show the error, though you may want to restart it after you’re done playing around in the config file. Of course, if you did have to restart the SSH server, you’ll need to do so again after fixing the error you intentionally introduced.

BONUS: If you want, you can list the path and check a configuration file that’s not actually in use. So, you can check the configuration file before putting it into production. That’s just:

1 | sudo sshd -t /path/to/new_config |

Again, under normal circumstances, it won’t show any output if it finds no errors. It only outputs information if there’s actually an error. So, a null response is considered normal and good.

Closure:

See? Nice and easy. Now you can check your SSH server configuration for errors – even doing so before putting the config into production. It’s a pretty handy tool to have. Also, you’ll need SSH installed and running on the machine you’ll be testing with. I figure that’s obvious, but I better mention it somewhere or someone will point it out or ask about it. Then again, people seldom read this far down in an article.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.