Today’s article will be easy to follow and is for those who’d like to show USB devices in a GUI in Lubuntu. Though truth be told, this is applicable for other distros. I’ve just tested it on Lubuntu and Linux Mint.

I want to assume that all my readers are familiar with USB. There are all sorts of things that can use USB, which stands for Universal Serial Bus. You can plug in USB storage, fans, power devices, and (with USB C) even connect external monitors or graphics cards. The standard has existed since 1998 and the most recent version is USB4. It has come a long way.

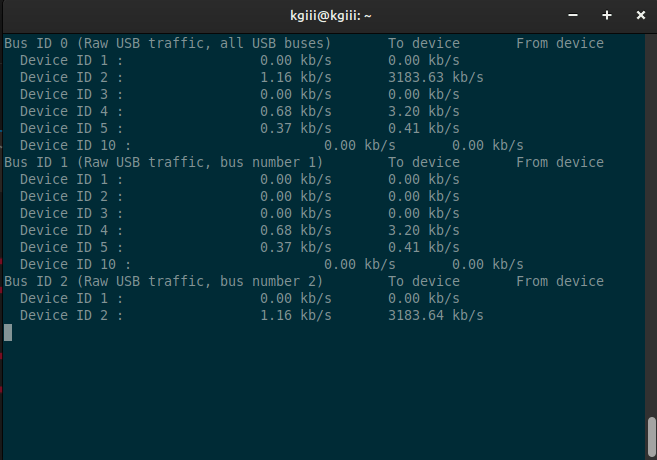

Linux is pretty good at enumerating USB devices and can use many of the various USB-powered tools. It’s possible to show the USB devices in the terminal, of course. I just figured I’d cover a way to do so graphically. You never know who wants to show USB devices in a GUI, so why not cover it in an article?

I’ve covered ways to show USB devices before. I’ve done so multiple times, so it seems. Click one of the links below to view another article.

Show Your USB Devices In The Linux Terminal

A Little About The ‘lsusb’ Command.

How To: List USB Devices

As this article is for Lubuntu, I’ll give directions as though you’re using Lubuntu. This is going to work on any Debian/Ubuntu-based operating system. The tool we’ll be using is also available for Arch and, I assume, other package managers.

So, what will we be using?

usbview:

We’ll be using a small application known as usbview. This is available in your default repositories and is easy to install. I’ll cover the installation methods below.

If one were to check the man page, you’d see it’s the right tool for the job.

usbview – display information on USB devices

Further, you can see this on the man page:

No command line options are accepted by usbview.

So, usbview a graphical (GUI) tool. There are no options for the terminal – but you’ll need to start it from a terminal. For reasons beyond my knowledge, there’s no application menu added when you install usbview. That’s something to keep in mind. It’s a GUI tool – but you start it from the terminal. Got it? Good!

Show USB Devices In A GUI In Lubuntu:

As mentioned above, you’re going to need an open terminal. As you’re using Lubuntu, you can just press

With your terminal open, you first install usbview…

1 | sudo apt install usbview |

That’s nice and simple.

Now, you can run usbview with this command:

1 | sudo usbview |

Yes, you need elevated permissions. It throws an error otherwise.

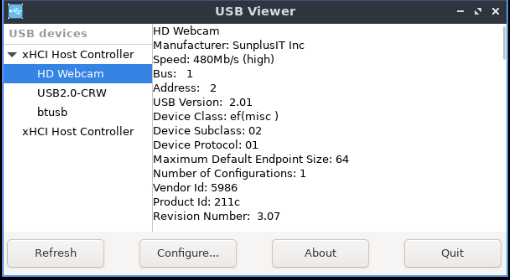

You’ll get a new window that looks something like this:

You can not only view USB devices, you can learn more about them. There’s not much to configure and you can ignore all the buttons except the Quit button. You’ll want that to quit the application.

But, there you go… That’s how you show USB devices in a GUI in Lubuntu!

Closure:

Anyhow, now you’ve learned how to show USB devices in a GUI in Lubuntu. This is a good thing and something you can trivially apply to other distros. I’m sure there’s a way to build usbview if you don’t already have usbview in your repositories. If graphically viewing USB devices is your goal, usbview is a possible solution.

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.

Seeing as you’re here, why not visit our friends at Blunix?

Here’s why you might just want to visit Blunix:

“Blunix GmbH offers Debian and Ubuntu focussed Linux Emergency Support 24/7, Project-based Linux Consulting, FOSS-based Managed Hosting on your company IaaS provider account as well as custom Training and Workshops. We prioritize fair business partnerships and employee quality of life over profit. We focus on reasonable security by default and encourage your employees and developers to keep things secure enough to avoid 99% of security issues with automated attack vectors. We focus exclusively on this and do partner with other companies to refer customers that do not fit exactly what we do, or where we require additional help (for example we have a security-focused company that we partner with for higher risk factor hosting setups).”

Click to visit Blunix GmbH.