Today’s article is going to show you how to transfer files between computers by using a quick Python server. It’s remarkably easy! It’s a temporary server (usually) and lasts only as long as you need it to.

Why would you do this? Well, you can transfer files from one computer to another. It also functions as an HTTP server which makes it easy to test things like simple web pages quickly and easily.

Are there better options? Quite probably. If you want to transfer a single file, then SCP is a good way to go about it. If you want to transfer multiple files, you could setup SFTP. If you want to test web pages, you can likely just write the files locally and then open them up with the browser of your choice.

You have options! And, thankfully, Linux provides all sorts of options – including setting up a quick Python server. As I said, it’s actually pretty easy.

A Quick Python Server:

This article requires an open terminal, like many other articles on this site. If you don’t know how to open the terminal, you can do so with your keyboard – just press

The first command I want you to run will let us know what version of Python you have installed. Many distros have (at present) moved onto version 3, but some still have Python 2 installed. So, for that information you just run:

1 | python -V |

Now, if you have Python v. 2.x, you would use this command:

1 | python -m SimpleHTTPServer |

If you’re using Python v. 3.x then the command you’d use is:

1 | python3 -m http.server |

(If you’re curious, the -m is telling Python which module to open.)

Anyhow, you can now connect to your server with the following command:

1 | ip.address.of.desktop:8000 |

Read how to find your IP address. Instead of an IP address, you can also use your hostname.

Anyhow, you now have a server running on port 8000. If you want to, you can also change the port number. This is the same for both commands. In both cases, just append your chosen port number to the command. Like this:

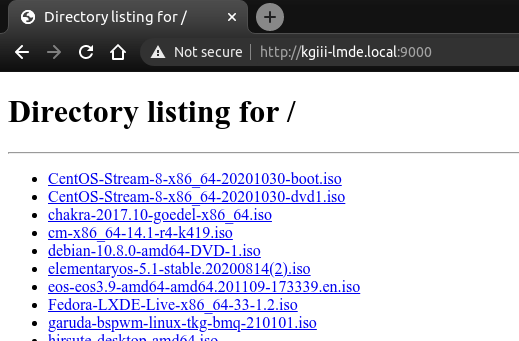

1 | python3 -m http.server 9000 |

It’d look a little like this:

When you’re done with the quick Python server, you can just close it by pressing

Like I said, it’s a quick and easy server in Python. You definitely wouldn’t want to use this as a public facing server, but it’s fine for quick tasks. Feel free to leave a comment letting folks know how you use this in your day-to-day tasks.

Closure:

There you have it, another article said and done! The site is going well and the schedule seems to be working well enough. It’s a bit demanding to write one every other day, but that’s what I said I’d try to do. So far, so good!

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.