Today’s article will be a fun and easy one if you already understand nameservers, as I will be explaining how to find a site’s nameservers. If you don’t understand nameservers, it may be a bit more difficult. But, I’ll do my best to make it approachable. So, to learn how to find a site’s nameservers read on!

Okay, so what are nameservers?

Hmm… Let’s try to explain it in the most simple way possible…

DNS is like a phone book. You look in the book to see which number (IP address) to connect to. However, just like in the real world (though less common with cell phones) a given telephone number may belong to multiple people.

Nameservers help to organize those DNS records. Using the nameservers is sort of like calling a phone exchange and then entering a party’s extension number to go directly to that person.

Does that make sense? No? Well, that’s the best you’re getting. I suck at analogies unless they’re automotive-related and I can’t come up with one that makes sense. I’m pretty sure the above was how it was first explained to me, or something like that. Ah well…

It should be pointed out that I used ‘dig’ in the previous article. We’ll be using that again. This time, we’ll be using dig to find a site’s nameservers instead of the site’s IP address. We might as well learn about it now, while the dig command is fresh in our memories!

Find A Site’s Nameservers:

This article requires an open terminal, like many other articles on this site. If you don’t know how to open the terminal, you can do so with your keyboard – just press

With your terminal now open, the syntax for finding a site’s nameservers is as follows:

1 | dig NS <domain_name> |

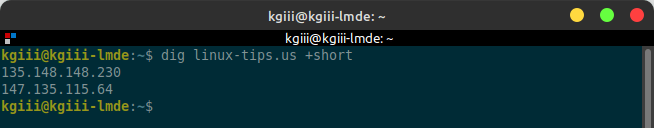

Or, if you prefer a shorter output, you have:

1 | dig NS +short <domain_name> |

Like the previously used dig command, you can actually put the flags at the end (if that’s something you feel like doing). It works just fine like:

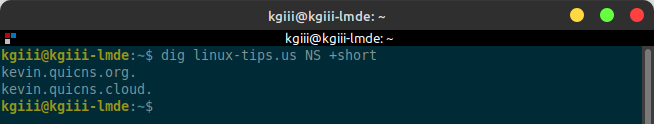

1 | dig <domain_name> NS +short |

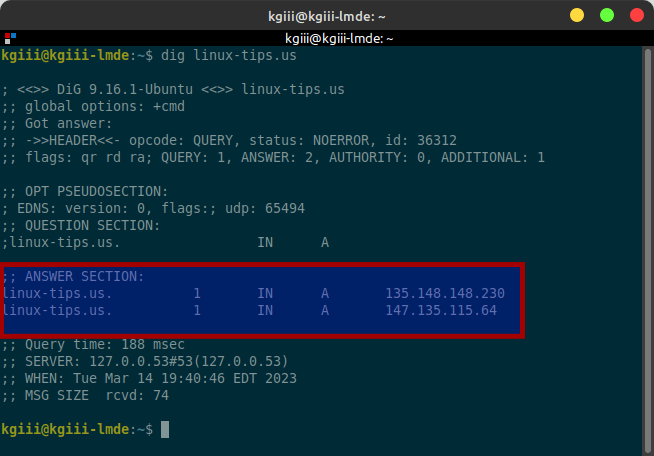

If we use this site as an example, the outcome of the latter command should look something like this:

As you can see, nameservers look just like domain names. You’ll also note that those (shouldn’t) don’t change, unlike the site’s IP address. As we’re using a CDN, there are a number of possible IP addresses. The nameservers will be the same no matter what part of the globe you connect from.

Of course, there’s more to the dig command. We’ve just touched on a couple of uses. Check the man page with man dig to find out what other options are available.

Closure:

Well, there you have another article. Once again, we’ve used dig in this article. I figured we might as well have another dig article while I was thinking about it, and this time we used dig to find a site’s nameservers. Hopefully, this will be useful for you at some point in your Linux journey. As I deal with a bunch of websites, it’s important for me to know my nameservers and to know when they’ve propagated (something for another article).

Thanks for reading! If you want to help, or if the site has helped you, you can donate, register to help, write an article, or buy inexpensive hosting to start your own site. If you scroll down, you can sign up for the newsletter, vote for the article, and comment.